[ad_1]

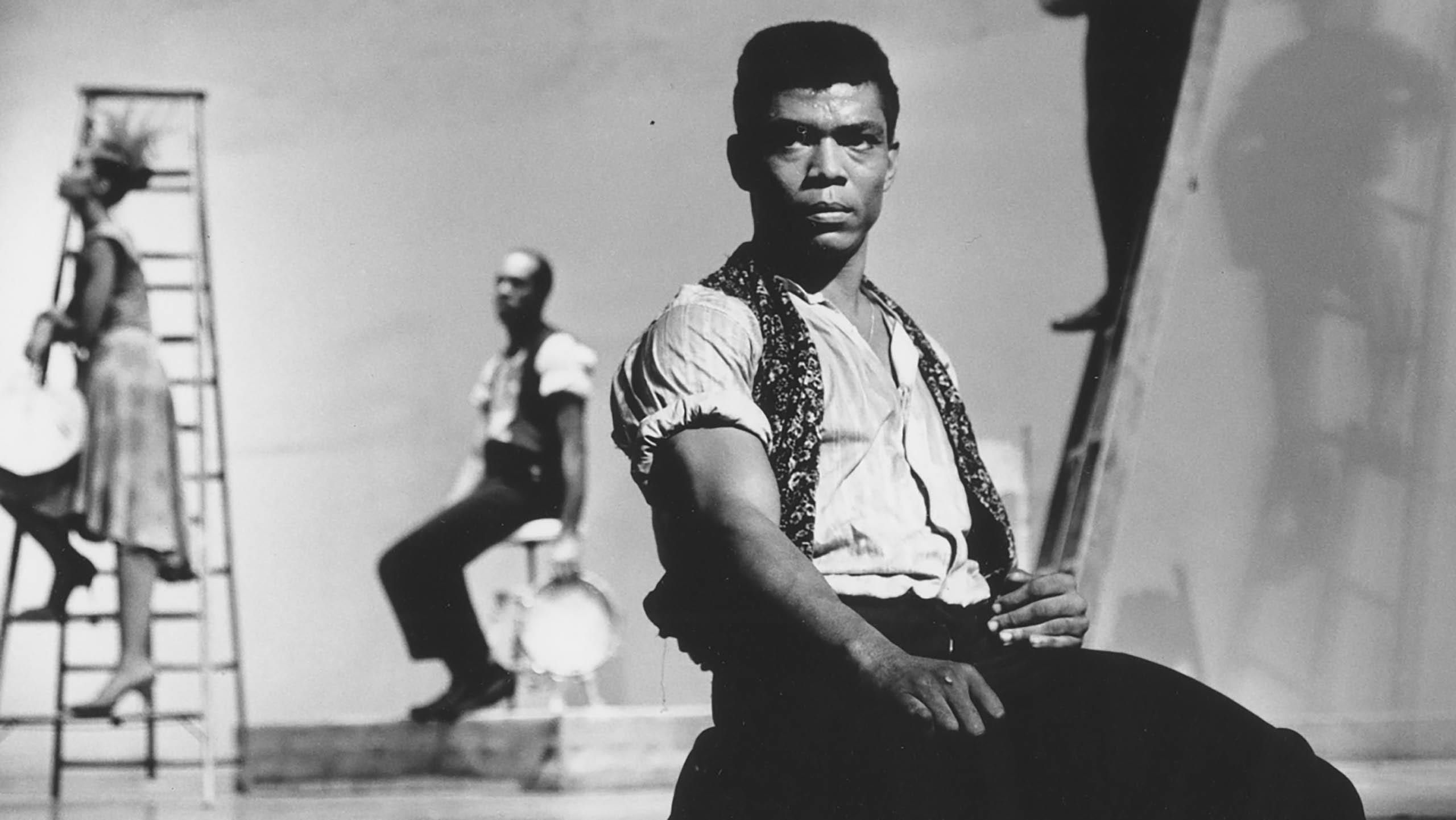

A still from Ailey, directed by Jamila Wignot. Courtesy of Sundance Institute | photo by Jack Mitchell

Some time during the first season of Sesame Street, the show’s primary producer, head writer and director Jon Stone approached musical director Joe Raposo with an unusual request. Could he write a song for the increasingly popular Muppet character Kermit the Frog to sing in the moments when the felt amphibian was feeling quiet and introspective? The Harvard-educated Raposo considered the assignment for a minute, hit a minor chord on his piano, and “It’s Not Easy Bein’ Green†began to flow out.

The song would go on to be sung by Lena Horne and Ray Charles, becoming a modest civil rights anthem in the process. It was yet another feather in the cap of Raposo, a close friend of Sinatra’s whose Children’s Television Workshop material became the soundtrack for many of our childhoods. (“Sing†even became a #3 hit for The Carpenters.) But the anecdote also highlights Stone’s unique skill for inspiring remarkable moments of genius from artists to help create one of the most significant and longest-running shows in television history.

Overshadowed both in life and death by collaborators like Raposo and, most significantly, Muppet creator Jim Henson, Stone is rescued from relative obscurity by Street Gang: How We Got We Got to Sesame Street, a documentary directed by Marilyn Agrelo (2005’s Mad Hot Ballroom) and based on Michael Davis’ bestselling book.

A still from Street Gang: How We Got To Sesame Street, directed by Marilyn Agrelo. Courtesy of Sundance Institute | photo by Robert Fuhring

Agrelo’s film is one of several documentaries that played at the recent Sundance Film Festival that sought to celebrate, understand, and contextualize major works of American pop art and the figures behind their creation.

The Summer of Soul, Questlove’s remarkable U.S. Grand Jury and Audience prize–winning documentary about a culture shifting music festival in 1969 Harlem has garnered most of the heat and attention coming out of the festival. But it was not the only Sundance documentary focussed on the creation of 20th century American popular art and the cultural forces that helped shape it. Alongside it and Street Gang, there was also Edgar Wright’s The Sparks Brothers, the Baby Driver director’s deluxe boxed set of a tribute to the long-lived LA art pop duo Sparks, and Jamila Wignot’s Ailey, a transcendent evocation of 20th-century America’s greatest choreographer.

Taken together, Street Gang, Ailey and The Sparks Brothers speak to the necessity of creation, as well as the loneliness and isolation that is all too often visionary art’s fertile field. Sesame Street’s Stone struggled with depression. Ailey possessed a profound sadness and anger that he could spin into art but which kneecapped his prospects for happiness in his personal life. Meanwhile, Russell and Ron Mael, the two brothers behind the six-decade-spanning cult pop band Sparks, seemed to live largely free of the Behind the Music-style tragedies that normally beset outfits of their ilk, but their ferocious need to push back against everything—the record industry, their fans, even themselves—speaks to the extreme insulation of the creative trailblazer.

“Creation is a lonely place,†a retired dancer says of Ailey towards the end of Wignot’s film. “It’s lonely because there is no one there who can help you.â€

|

STREET GANG: HOW WE GOT TO SESAME STREET ★★★1/2 |

By shining the light on Stone, Agrelo’s movie rightfully makes a national hero out of a historical footnote. Frank Oz, who was not interviewed for the documentary, has called Stone the “soul†of Sesame Street. Stone authored There’s a Monster at the End of This Book, the Grover-starring classic that has sold over 13 million copies, and has long been acknowledged as one of the TV’s most accomplished writers for children.

But Street Gang goes one step further. It makes a convincing argument that the irascible writer/producer/director pulled off what is perhaps the greatest feat of television making known to man. Certainly Stone was the medium’s greatest alchemist.

Not only did he hire Henson and Raposo as well as most of the show’s cast and writers, he devised the concept of having it all take place on a city street. Most miraculously, Stone expertly juggled the show’s twin missions of preparing 2- to 5-year olds for school while entertaining the hell out of both them and their parents. It was a job that required balancing the needs of a team of gag writers who would rather be peddling their wares for The Tonight Show with the seemingly at odds demands of educators and philanthropists focused singularly on bridging the opportunity gap facing Black and brown communities.

Placing Jon Stone in the firmament of TV’s greatest creators is a noble mission for Agrelo’s film; it’s a necessary one as well. Without it, the film, from HBO Documentaries and streaming on HBO Max later this year, might begin to resemble a feature-length commercial for one of the streaming service’s pricier acquisitions. (HBO Max became the exclusive home to new episodes of Sesame Street starting with its 51st season last year.)

It was not by accident that it’s as Sesame Street was breaking barriers in television representation in their studio in Queens, across town in Manhattan, the dancers at Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater were creating some of the most powerful and lasting artistic expressions of the Black experience in this country’s history.

Indeed, just as Sesame Street was embarking on its second season, Ailey was debuting Cry, his gift to his mother and an ode to all Black women; it was an 18-minute solo famously danced by the company’s future Artistic Director Emerita, Judith Jamison. The footage of that dance and Jamison’s impossibly lithe, immeasurably strong and profoundly emotional movements were as evocative and affecting as anything I saw at the festival this year.

A still from Ailey. Courtesy of Sundance Institute | photo by Jack Mitchell

At the same time, witnessing the creation of some of Ailey’s most iconic choreography during our own time of racial reckoning felt nearly as dispiriting as it did inspiring.

|

AILEY ★★★★ |

Ailey and his movements—he’s described in the film as a train that changes the geography around it as it moves through space—are such a pure expressions of Black joy and truth. Every plié and arabesque overflows with possibly, with the dancers’ outstretched hands reaching towards a more perfect future that seemed very much on the horizon. That so many decades later we have made such little societal progress on the entrenched injustices that Ailey transforms into beautiful art feels shocking and deeply sad.

The most accomplished of the three films, with Ailey, Jamila Wignot (2013’s Town Hall) masterfully weaves the present with the past in a way that causes her movie to surge with urgency. As the current Ailey company rehearses a new dance in his honor, we learn about his childhood growing up poor and fatherless in small-town Texas. He found refuge in church and honky tonks, seminal experiences that he would pour into his most well-known and widely performed work, 1960’s Revelations.

For a movie that pulses with joyful expressiveness and brims with possibility, there is a tragic undertone to Ailey, which was acquired by Neon during the festival. A gay man who was never public about his relationships and died of AIDS-related illness in 1989, Alvin Ailey was someone who showed the myriad possibilities in which body and movement could connect people and experience, but he never found connection himself, at least not within the gay community.

A still from The Sparks Brothers, directed by Edgar Wright. Courtesy of Sundance Institute | photo by Jake Polonsky

The Sparks Brothers, Wright’s first foray into nonfiction filmmaking, is a celebration of that strange, wonderful and weird connection that many of us feel when we listen to pop music. It tells the story of two brothers who grew up middle class in Santa Monica and the Pacific Palisades playing football and surfing and who were somehow transformed after a few semesters at UCLA into avant-garde pop musicians who would be more at home in the Weimar Republic.

|

THE SPARKS BROTHERS ★★★ |

While I consider Sesame Street a central part of my early identity, and have always held up Ailey and his work as an expression of American artistic exceptionalism rarely matched outside of a handful of jazz musicians, I had never heard of Sparks. (This despite having once been employed by Rhino Records A&R head and Apple Music Chief Music Officer, the late great Gary Stewart, one of the film’s chief talking heads and lead Sparks evangelist.)

Yet by the time Wright’s somewhat exhaustive film concluded, every moment of it propelled by a high-octane geeky affection that felt like a newly discovered alternative fuel, I was in the strange duo’s thrall. It had less to do with the glam synth music they created—which had its moments but I could generally take or leave—than how unclassifiable and inscrutable they are, boldly defying Wright’s desperate attempts to pin them down.

While Sparks can’t be categorized, the same can’t be said about the homogenous talking heads with whom Wright chooses to speak. From Todd Rundgren to Steve Jones to Jason Schwartzman to Wright himself, it feels like the director sourced his interviews from the latte queue at the Melrose Urth Caffe.

Of course this speaks to a problem that often face documentarians that dare to contend with the legacies of singular artists. By featuring people sitting in chairs speaking passionately about a beloved collaborator’s singular genius, the result is notably conventional despite the uniqueness of their subjects. Only The Sparks Brothers, which as of press time had yet to pick up distribution, had the benefit of having the subjects speak on behalf of themselves, and they provide more color and quirk than real insight.

But the way that all three movies face head-on their central mystery—why are some driven to sacrifice so much to wrangle with the isolating newness of creation while the rest of us are satisfied with what we have?—with a boldness of purpose allows them to teem with vitality despite their traditional presentation.

The uniqueness of their subjects helps. So does the fact that all three films—just as Questlove’s The Summer of Soul does—capture the vigor and ineffable spark of live performance.

This is true when watching the modern Mael brothers take on the Herculean task of recreating all 21 of their studio albums in order to play them in order during a residency in England; seeing the anger and love shoot forward from the movements of Ailey, Jamison, and the other dancers in his company; or watching the late Carroll Spinney, dressed as Big Bird, paying tribute to Jim Henson at St. John the Divine in May of 1990, just five days after the puppeteer’s still-shocking death. (Jon Stone was one of the eulogists.)

His voice choked with emotion, Spinney said goodbye to his friend by singing Joe Raposo’s “It’s Not Easy Bein’ Green.†I imagined Spinney, soaked with sweat inside his costume in the hot and crowded cathedral, his arm jutted high in the air to control Bird’s eyes and beak.

How did he do that? I thought as I watched the footage in Street Gang, home alone just as I watched everything else in this strangest of Sundance years? How is that even possible?

Then I thought, Thank God we get to witness it all over again.

Observer Reviews are regular assessments of new and noteworthy cinema.

[ad_2]

Source link