[ad_1]

After a year on ice, Britain’s labour market is rapidly unfreezing.

Hospitality employers are scrambling for staff; bin crews are being poached by delivery companies; and white-collar workers are in demand as companies switch from survival mode and relaunch projects to drive future growth.

Employers already struggling to recruit may soon find it harder to hang on to existing staff: people who last year hesitated to leave the safety of a stable job are now scouring the website of the charity Citizen’s Advice in record numbers for guidance on resigning.

“Demand is really high. There are really substantial reports of shortages in hot sectors of the economy,†said Neil Carberry, chief executive of the Recruitment & Employment Confederation.

These emerging labour shortages — compounded by Brexit — raise the possibility that, after a long period of wage restraint and precarity, workers will finally wield more bargaining power.

“It’s been a buyers’ market for a long time in the labour market and employers haven’t had to work too hard to attract and retain people in lots of low paid areas,†said Tony Wilson, director of the Institute for Employment Studies. “For the first time in a decade, it is more of a sellers’ market.â€

In some areas, hourly pay is starting to rise. Pawel Adrjan, economist at the jobs site Indeed, said the median advertised rate for pub and restaurant jobs had risen from £9.25 to £9.35 since the first quarter, while in social care it has climbed from £9.51 to £9.71.

There have been steeper increases for the highest paid driving roles, likely to reflect a chronic shortage of qualified lorry drivers, which has been exacerbated by Brexit, a backlog of driving tests, and changes in tax for contractors that added to the outflow of EU drivers.

“We’re not at the point where the dust has settled yet,†said Kieran Smith, chief executive of the recruitment agency Driver Require. In the past, customers had forced down margins in the haulage industry to “almost unsustainable levelsâ€, but now, “if they wish to have a delivery and a driver, the agency can dictate the rateâ€.

Mick Rix, a national officer at the GMB union, said higher pay for drivers would soon lead to similar demands from warehouse staff, as pay deals are negotiated over the next few months.

But Indeed has seen few signs of pay rising in other sectors, even those that have been hiring rapidly, with median wages flat in warehousing, retail, cleaning and less skilled driving roles.

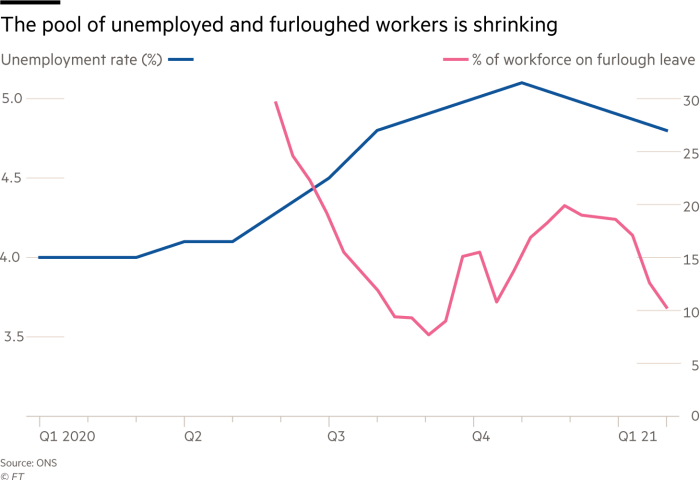

“It isn’t entirely surprising. Most employers may be viewing the current hiring bottlenecks as temporary, given how many people are still unemployed or on furlough,†Adrjan said.

In hospitality, employers are finding that people are unwilling to leave the shelter of furlough — which ends in September — or of more stable sectors, for a job in which they would not qualify for wage subsidies if a new lockdown struck.

“If they move now, they lose that safety net,†said Kate Nicholls, chief executive of the trade body UKHospitality.

Some companies are therefore offering guarantees of job security, rather than higher pay: Carberry said one major pub chain had promised new staff they would be furloughed in any fresh lockdown.

Many businesses in low margin sectors where long shutdowns have left them cash-constrained said they could not afford to pay more.

“We can’t raise wages,†said Joe Cobb, commercial manager at Lake District Country Hotels, who discovered a week before reopening his three properties that 10 per cent of his staff did not plan to return — mostly EU nationals who had gone back to their home countries.

Operating in an area with few young people, the company has tried other ways to make jobs more attractive: building accommodation for staff who cannot afford local rents; changing its shift patterns; and offering staff discounts. It has also advertised apprenticeships paid at the adult rate for the past four years — without attracting a single application.

Many more employers are now under pressure to improve job security, flexibility and career structures — which may matter as much or more to potential recruits as an increase in pay.

One clear shift in the balance of power is the new ability of white-collar workers to demand flexibility in when and where they work.

“One of the first questions is, does the company allow agile working?†said Habiba Khatoon, director for the Midlands region at the recruiter Robert Walters, adding: “Clients are open to it because they see it is the only way to stay competitive.â€

Less clear is whether employers are ready to make meaningful changes in sectors where poor working conditions are endemic.

In haulage, “the sector is its own worst enemyâ€, said Drive Require’s Smith, who thought pay will have to rise sharply to lure back qualified drivers who had moved into less gruelling jobs with steady hours.

Yet in hospitality, employers are starting to offer more flexible terms and different ways of working, Nicholls said, with part time hours, flexitime, and shifts that suit working parents.

This is partly because they need to tempt back workers who have joined other sectors in the last year. Kim Teagle, recruitment manager at Bluebird Care, a UK-wide domiciliary provider, has hired people from hairdressing and hospitality who plan to stay with the company, observing: “They didn’t realise how secure a job in care is.â€

But she admitted her company was able to offer staff better terms than most rivals because it did not rely on public funding. For others in the sector, which suffers chronic recruitment problems, “unless money’s put into it, it’s not going to changeâ€.

Yet Carberry argued the labour crunch would not be a passing phenomenon. Over the next decade, demographic pressures and slower migration mean Britain’s labour market would be tight, he said, forcing employers to think about pay, working conditions and careers.

“We’re expecting quite a fundamental shift towards there being more of a candidates’ market,†he said. “I foresee shortages for some time to come.â€

[ad_2]

Source link