[ad_1]

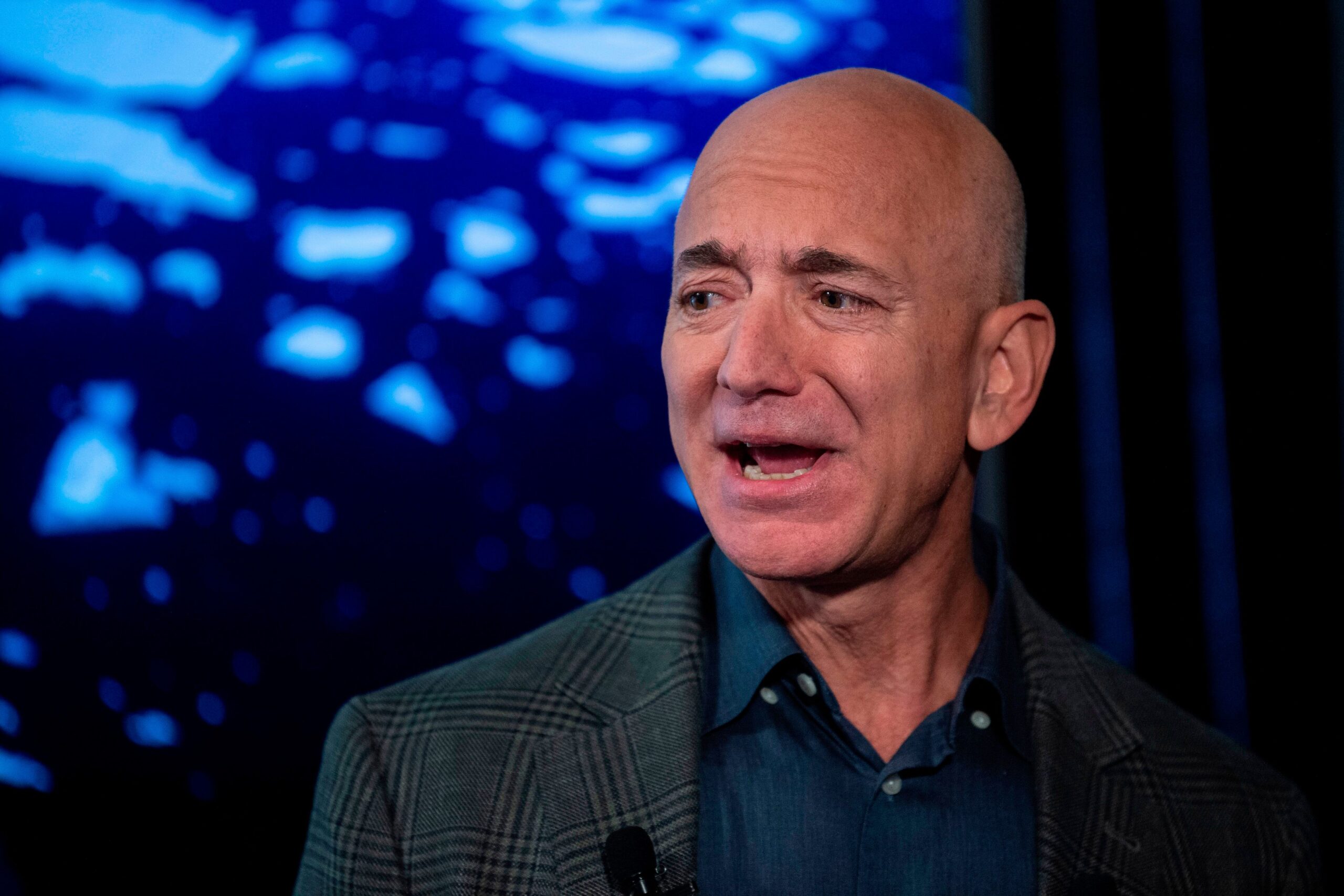

Amazon Founder and CEO Jeff Bezos speaks to the media on the company’s sustainability efforts on September 19, 2019 in Washington, DC. (Photo by Eric BARADAT / AFP) (Photo credit should read ERIC BARADAT/AFP via Getty Images) ERIC BARADAT/AFP via Getty Images

As a vast majority of the American populace sat at home, worried about dwindling savings, sick relatives, or when the beleaguered USPS might finally deliver their seven packages, Amazon, already one of the world’s biggest companies, reaped record profits.

The online everything store’s profits swelled by about 20 percent from the start of the pandemic last March through December. The value of shares in company stock increased 70 percent, a windfall that swelled CEO and founder Jeff Bezos’s fortune by an astounding $75.6 billion.

Amazon’s nearly 1.2 million workers, tens of thousands of whom contracted COVID-19 while on the job, got an average hourly pay increase of about $1 an hour.

Amazon is not unique in the vast inequity in how executives chose to split the pandemic-charged profits. Most every major American company staffed by “essential workers,†who kept clocking in during the pandemic, including Wal-Mart and Walgreens, also divided the spoils of the plague in ways that exacerbated the yawning gap between low-level frontline workers and executives.

While creating immense wealth, the stark juxtaposition has created immense grievance, and with it, growing awareness among workers within Amazon’s sphere at fulfillment centers and Whole Foods locations.

That means Amazon also accidentally created the best opportunity for organized labor to increase union membership in decades, labor experts and organizers say.

“The odds of the current moment being a turnaround point for the labor movement are the highest they’ve been in years,†said John Budd, a labor expert and professor of work and organizations at the University of Minnesota’s Carlson School of Management. “But that might say more about how disadvantaged the labor movement has been for a long time.â€

Membership in labor unions has steadily declined since the 1980s, when President Ronald Reagan dealt harshly with striking air-traffic controllers and ushered in an era that favored business over workers. Years of free trade deals also stripped unions of much of their negotiating room.

Just 10.8 percent of American workers were in labor unions in 2020, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, down from 20.1 percent in 1983. And with the advent of gig work, like “5 to 9†side hustles and companies who rely on freelance contractors—the human machines that power companies whose operations continued throughout the pandemic, like Uber and Doordash—more workers than ever grasp how perilous their existences are.

See Also: Amazon Is Sending More People to Work in Offices, Despite Dire Pandemic Outlook

Outrage over low pay in exchange for high risk is a key reason why the nearly 5,800 people employed at Amazon’s fulfillment warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama are currently voting whether to join the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union.

The vote runs through March 29. In a sign of both Democratic and Republican politicians recognizing the backlash by struggling workers against enormously profitable companies, President Joe Biden and Republican Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL) have both come out publicly in support of the union drive (even if Rubio’s support was steeped in culture war rhetoric).

If the vote is successful, the union must then negotiate a contract with Amazon—no small feat with a company that’s proven remarkably adept at defeating union drives.

“That those workers have stood up to Amazon in the south during a pandemic can be an inspiration to many others,†Budd added, “but being able to point to tangible gains won in a contract would make it easier for activists in other workplaces to get others to join them.â€

In Chicago, Amazon workers early in the pandemic already felt empowered enough to organize “safety strikes†over hazardous working conditions—and as The Intercept recently reported, the National Labor Relations Board ruled that the company illegally retaliated against the workers involved. This could be a sign of shifting power alignments in Washington, DC., or at least give encouragement to workers pondering organized action in similar circumstances.

See Also: Jeff Bezos Can’t Remember His Great Diaper Chase In Congressional Testimony

Bezos declined to accept an invitation to a hearing on wealth inequality in the US Senate Banking Committee held by Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT), who excoriated him and his company in absentia.

“If he was with us this morning, I would ask him the following question … Mr. Bezos, you are worth $182 billion — that’s a B,†Sanders said on Wednesday. “One hundred eighty-two billion dollars, you’re the wealthiest person in the world. Why are you doing everything in your power to stop your workers in Bessemer, Alabama, from joining a union?â€

But organizers say whether Amazon wins or loses in Bessemer, the lesson of the COVID-19 pandemic and its unequal profits is something workers across the country will remember for a long time.

In 2017, Amazon acquired Whole Foods for $13.4 billion. Union organizers immediately critiqued the purchase. “Amazon’s brutal vision for retail is one where automation replaces good jobs,†Marc Perrone, president of the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union, said at the time. “That is the reality today at Amazon, and it will no doubt become the reality at Whole Foods.â€

In the nearly four years since, current and former Whole Foods employees, organized with a non-profit labor union called Whole Worker, have tried to unionize Whole Foods locations. In their view, the development at the Alabama Amazon warehouse should make organizing efforts at Whole Foods easier—and could portend union drives elsewhere in the Amazon empire as well as at unrelated companies in similar conditions: Trader Joe’s, even Wal-Mart.

“I would say we’re probably approaching some inflection point,†said an organizer and current Whole Foods employee who gave their name as “Glamazon Prime†in order to protect their real identity for fear of retaliation. “I do believe that the vast majority of people who work at Amazon want a union or at least recognize the unfairness of the situation that we’re in.â€

“I think the biggest obstacle to organizing is that a lot of people feel it’s hopeless to try to organize against Amazon—they’re so big and powerful and they’ve managed to escape consequences for so long,†the worker added. “But I think the moment any workplace within the Amazon sphere gets unionized it will be proof of concept. As soon as people see one store, one warehouse unite and stand up, much more will come out of the woodwork pretty quickly. It will have an enormous ripple effect if the union vote goes through.â€

Behind the Bessemer vote looms the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic shifted buyers’ habits towards online purchasing—and served as both triggering event and accelerant for union drives, experts said.

“The COVID pandemic really laid bare to a large number of workers how little they matter to their employers,†said Ken Jacobs, chair of the Labor Center at the University of California, Berkeley. “Employers may call them essential, but they see how little regard they have for their lives and well-being.

“I think that’s one reason why you’re seeing an increase in support for unions, and a demand for unions.â€

[ad_2]

Source link