[ad_1]

From the construction in Ethiopia of the world’s 10th-largest hydropower dam to solar-powered homes in Senegal, many African countries are pushing to achieve better access to energy for businesses and consumers. But while some have made big strides in electricity provision in the past decade, 600m Africans remain unconnected to the grid.

Supply challenges persist because of outdated or non-existent infrastructure. The resulting blackouts increase the cost of doing business, stifling investment in manufacturing and other industries. And, because their public utilities are already indebted, governments are tempted to tax start-ups that might otherwise provide alternative, off-grid solutions — which hinders the adoption of new technologies in rural areas.

“While sub-Saharan Africa is the world’s poorest region, it has some of the highest costs of electricity,†says Philippe Benoit, adjunct senior research scholar at the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University SIPA. “Often, people are paying for grid electricity as well as a back-up generator in order to have [several] hours of reliable power.â€

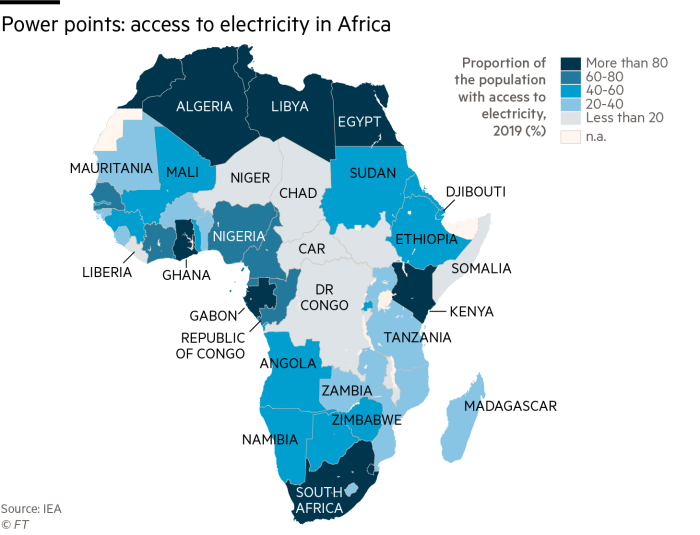

Access to electricity varies greatly across the continent. In Morocco, some 99 per cent of the population has access to electricity, while in the Central African Republic the figure is as low as 3 per cent, according to the International Energy Agency. Retail prices also vary: the cost of a megawatt hour of power is $490 in Liberia, but $46 in Zambia, according to data company Statista.

Some of this variation is down to governance, says Benoit, who has worked on power projects in the Democratic Republic of Congo and in Ethiopia.

Fifteen years ago, both countries, which have significant hydropower potential, had similar access rates: with 7 per cent of the DRC population having access to power, and Ethiopia 12 per cent. Today, Ethiopia has reached 47 per cent, while the DRC has crept up to 9 per cent, says the IEA.

“Government matters,†says Benoit.

$5bn

Value of annual electricity transmission and distribution losses in sub-Saharan Africa

One of the main challenges in expanding access to electricity in sub-Saharan Africa is poor transmission and distribution infrastructure. A study by the Ghana Institute of Management and Public Administration published in November 2020 showed that electricity transmission and distribution losses — when energy escapes low-voltage distribution lines in the form of heat, for instance — in sub-Saharan Africa amounted to $5bn annually. South Africa accounted for $1.5bn of that.

Zainab Usman, director of the Africa Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, points to a “fixation†with investing in infrastructure for power generation, while leaving transmission and distribution unÂaddressed: “A lot more investment needs to go into systems that can actually handle the upsurge of power that is to come.â€

The $4bn Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam — under construction on the Blue Nile by Ethiopia without the agreement of downstream countries Egypt and Sudan — will generate a forecast 6,450MW of hydropower.

The Ethiopian government has said some of the electricity will be sold to other countries, including Sudan, but the two governments would need to construct a transmission line from the dam to the Sudanese capital Khartoum, according to the African Union’s Programme for Infrastructure and Development. At more than 400km in length, the AU estimates the line would cost $1.8bn to build.

Usman says multilateral development agencies can help countries by studying the feasibility of a proposed project’s transmission capacity and, in some cases, financing it. But national governments must also ensure their systems are able to handle a higher electrical load and inÂevitable fluctuations in power supply.

One technological solution to low electrification rates in rural areas is mini-grids. Modern versions are powered by an energy source — usually solar panels — combined with battery storage and a local distribution system. Rwanda, for example, has achieved big improvements in electrification rates by employing mini-grids.

In 2015, only 20 per cent of the population had access to electricity; by the end of 2018, it was 51 per cent — and solar mini-grids were responsible for a third of that growth.

According to Faith Chege, east Africa portfolio co-ordinator at the Energy and Environment Partnership Trust Fund, which supports clean energy projects, the main barrier to more mini-grid and solar-home projects is unpredictable regulation in most sub-Saharan nations.

“For example, in Kenya, the revenue authority might decide . . . they need to get tax from somewhere,†she says. “So they hike up taxes on solar-home companies [where standalone photovoltaic systems cost-effectively supply power to a single house], which makes it a difficult environment to set up a business.

Lack of co-ordination between the private and public sectors is a further challenge. Mini-grid companies may establish a service in an area with no access to the grid only to discover, soon after, that the government is putting up transmission lines thanks to a World Bank-supported scheme.

More stories from this report

The Africa Minigrid Developers Association, an industry group, has been pushing for multilateral organisations such as the World Bank to give mini-grid developers the same subsidies as public utilities since they are cheaper, says Chege.

“During Covid-19, they’ve also shown they understand the customer much better than the utility does,†she adds.

Inequalities remain, though. Kenya now obtains more than half its electricity from geothermal energy and even has a surplus. The government is trying to stimulate electric vehicle demand to soak up the excess supply, Chege says. But, for many other African countries, surplus electricity is still a distant goal.

[ad_2]

Source link