[ad_1]

When US Steel released America’s first annual report more than a century ago, it was an admirably trim 40 pages, and mostly photos of smokestacks. Its 2020 annual report clocked in at 162 packed pages — and even this is concise by modern standards.Â

Public companies release reams of financial information and insight into their business every quarter, but the annual report is the big blue whale of corporate reporting. These days, the average length is the equivalent to a 240-page novel, according to S&P Global.

It is popular to bemoan that quarterly and annual reports are now word salads, consisting mostly of vast amounts of often useless reporting requirements and standardised legal caveats, and then sprinkled with a big dose of PR guff. The core accounting numbers have not changed meaningfully in quantity and quality over the past century, cynics complain.Â

It is true that corporate reports contain verbiage that would make even a journalist blush. But instead of heaping scorn on these reports, savvy investors should embrace this admittedly waffly textual information as a potential gold mine that can finally be mined with modern technology.Â

Historically, investing has primarily rested on a bedrock of numbers, such as stock prices and profits, revenues and research spending. Traditional stockpickers would naturally supplement this with plenty of qualitative analysis, such as interviewing a company’s chief financial officer, chatting to industry experts and poring through annual reports.Â

Yet the swelling volume of corporate statements means that no one can realistically consume everything. In the US, the “risk factors†section of annual reports has alone almost tripled in length since 2006 and now averages more than 11,000 words, according to a recent report by S&P Global. Still there are valuable signals hidden within even the subtlest changes, notes Frank Zhao, an analyst at S&P’s Market Intelligence team.

The tool to glean tradable signals from textual noise is known as ‘‘natural language processingâ€, an increasingly popular field of artificial intelligence that involves teaching machines how to read and understand the intricacies of human language. NLP allows tracts of previously recondite non-numeric “unstructured†data to be systematically harvested and analysed at dizzying speeds.Â

The potential is immense. Kai Wu, a former GMO analyst who now runs Sparkline Capital, a start-up investment firm, argues that many trading strategies built on traditional data are “tapped outâ€, after having been analysed to death for decades and now mined to oblivion. “But once you cross the Rubicon into the world of unstructured data, suddenly the fruit is hanging much lower,†Wu wrote in a paper last month.

Natural language processing-directed trading algorithms are particularly sensitive to certain words

Positive:

Proactively

Satisfying

Revolutionise

Negative:

Aggravate

Restated

Bottleneck

Uncertainty:

Anomaly

Appears

Clarification

Source: Loughran-McDonald dictionary

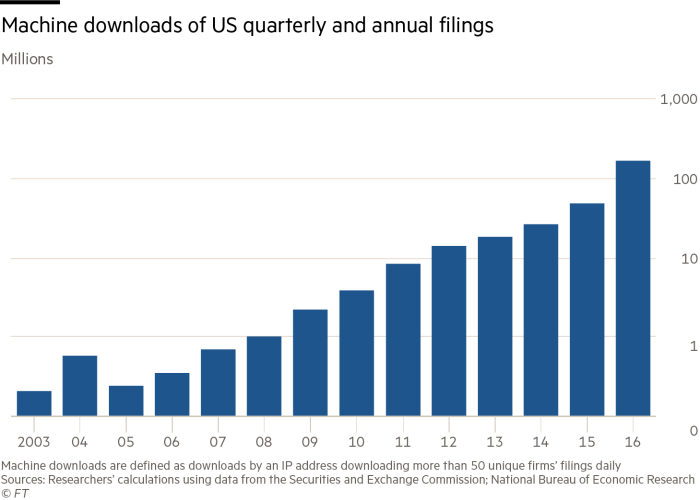

Many sophisticated quantitative investors — those that primarily use algorithms to systematically trade, rather than traditional human fund managers — are already grasping after this fruit. Last year, an NBER paper estimated that algorithmic downloads of quarterly and annual reports in the US exploded from about 360,000 in 2003 to 165m in 2016, when they accounted for 78 per cent of all downloads.Â

Since 2016 the rate has almost certainly soared further. Industry insiders say that there is nowadays a quasi arms race between NLP algorithms that scour corporate statements and company executives that attempt to outfox them by avoiding certain touchy words and phrases.Â

Yet in reality, NLP is an opportunity for all investment managers, not just quants that try to exploit textual signals systematically. For example, Nomura analyst Joe Mezrich has used an NLP system to scour through transcripts of corporate executives talking to financial analysts, grading the companies by their apparent adherence to ESG standards. He discovered that the stocks of the most ESG-compliant companies performed better than the broader equity market.

Quarterly and annual reports are now generally released in a machine-friendly format, but they are the tip of the iceberg of written information that investors can rummage around for valuable signals. Transcripts of management calls with analysts or TV interviews with chief executives, newspaper reports, central bank speeches or even social media chatter can all be mined.Â

The finance industry loves its buzzwords, and anything to do with artificial intelligence is particularly hot these days, and should be treated warily. But we might be at the beginning of a textual investing revolution that could upend the industry.

Twitter: @robinwigg

[ad_2]

Source link