[ad_1]

Welcome back. Do you work in an industry that has been affected by the UK’s departure from the EU single market and customs union? If so, how is the change hurting — or even benefiting — you and your business? Please keep your feedback coming to brexitbrief@ft.com.

Just when you thought it was safe to enter Whitehall, Wednesday’s Downing Street dust-up leading to the appointment of David Frost to the cabinet felt like a lurch backwards into the kind of court drama that was supposed to have ended with the departure of Dominic Cummings and friends.

There were furious denials that Frost had threatened to resign to win his seat at the top table along with the chairmanship of the joint partnership council governing the post-Brexit trade deal, but the fact that Michael Gove had been appointed “interim chair†only two days previously made it obvious that these moves were happening hastily.

This fight, by several accounts, had been brewing for a while as Dominic Raab’s foreign office made the case around Whitehall for the bilateral EU-UK relations to be repatriated to his department, but ultimately that was always a forlorn hope. Relations with Europe have effectively been run out of the centre long before even Brexit came along.

On the upside, the Frost appointment does at least clarify where power resides on EU-UK relations. He clearly has the ear of the prime minister and by simultaneously handing Frost control of the Northern Ireland protocol implementation, potential rivalry and confusion with Gove — who previously controlled that element of the deal — is also avoided.Â

And for civil servants caught up in the middle of all this — many who well recall the mess created by the rival power centres of Downing Street and the ill-conceived Department for Exiting the European Union — the clarity in reporting lines should be helpful at an operational level.Â

Frost’s elevation to the cabinet is also for the best. For too long Frost — a former Foreign Office official, turned Scotch whisky lobbyist and latterly political special adviser — has existed in a political grey zone. As Brexit chief negotiator, he was allowed to make policy speeches in Brussels, and yet was never formally accountable to parliament. That now ends.

But all that said, it is difficult to see Frost’s elevation as a move that will mollify relations between the EU and the UK, which — thanks to mistakes on both sides over vaccines and the implementation of the Northern Irish protocol — have got off to a tetchy start.

The problem is that Frost’s modus operandi with the EU has always been confrontation. He seems genuinely to believe that this is the best way to extract results and officials with close experience of working with Frost say he’s looking to “keep it confrontationalâ€.

In 2019, during the negotiations over the Northern Irish protocol, officials on both sides said it was Frost who advised that taking a tough line would get the EU to force Ireland to accept the creation of a technological north-south trade border in Ireland.Â

He was wrong, but ultimately that misjudgement was overtaken by the hasty creation of the Northern Ireland “front stop†that left Northern Ireland following the customs rules of a foreign trading bloc, but opened the door to the political triumph of Boris Johnson’s 80-seat majority in December 2019.Â

Having won that majority to “Get Brexit Doneâ€, there was then a second moment in early 2020 when the UK could have taken a less confrontational path. There was an option to extend the transition period, and then to seek the kind of mobility packages and regulatory alignments on chemical and medicine regulation that would have addressed many of the problems that industries and service professionals are now complaining about.Â

But again, the Frost-Johnson approach was headlong confrontation — threatening to renege on sections of the Northern Irish protocol and then signing a “Canada-style†trade and co-operation agreement (TCA) that from the outset prioritised sovereignty over market access.

Having done that deal, these first few weeks of 2021 provided a third pivot-point at which the Johnson government could have “moved onâ€, focusing its energies on the domestic levelling-up agenda and — as the EU ambassador the UK João Vale de Almeida put it this week — worked to embrace “life after Brexitâ€.

But given all that recent history, it would take a supreme optimist to read Frost’s appointment as a step in that direction. Instead it seems like another triggering of the Conservative party’s EU fight-reflex that has driven the Brexit process ever since Johnson ousted Theresa May.Â

To what strategic end remains unclear. Politically, confrontation might play well on the Tory backbenches — not giving full diplomatic recognition to the EU ambassador, for example — but the next year is going to be about real-world implementation of Brexit.

The first six weeks of this deal have generated a whirlwind of complaints as business discovers fully what it means — for product distributors, food exporters, SMEs and professional services — all of which are urging the government to work with the EU to better implement the TCA, limited in scope though it be.

In many ways — as Lord Hill observes in our long read this week on the future of EU-UK relations — confrontation is in-built in the EU-UK relationship, which creates a succession of pressure points by which Brussels can continue to exert its leverage.

In almost any scenario this was going to be tough, but it is difficult to see how confrontation helps address complaints from UK business. Pressure will only grow as pre-Brexit stockpiles expire and the UK starts to implement its own border controls in July, which will affect UK importers and exporters.Â

Add to that the coming unemployment surge as the Covid-19 furlough scheme expires and the minister charged with running the EU-UK relationship (that covers 48 per cent of total UK trade, lest we forget) is going to find himself in the operational, as well as ideological, cockpit of Brexit. I do not forecast a smooth ride.

Brexit in numbers

There was a time when Brexit just meant “Brexitâ€. Slowly but surely, however, a picture is emerging about what Brexit does actually mean, and how it is shifting EU-UK trade patterns.

With the usual caveats about this being early days, some data from an industry source on how Irish businesses are cutting out the UK “land bridge†by shipping direct from Ireland to the EU to avoid customs hold-ups is remarkable.

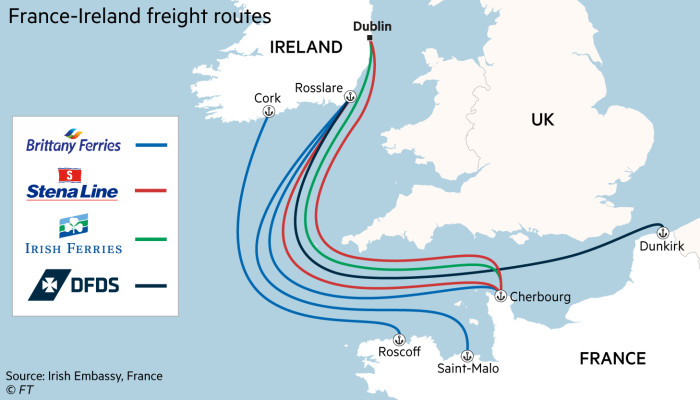

Fleet-footed shipping lines such as Stena have responded by redirecting capacity into new routes, like Dublin-Cherbourg, while boosting other routes, including by redirecting one ship destined for the Liverpool-Belfast route to work Rosslare-Cherbourg instead. Irish Ferries did something similar.

Roll-on, roll-off freight movements between Ireland and the continent this January have increased more than threefold (329 per cent) since last January. Even off a low base, that is a startling number.

Conversely, movements from the Republic of Ireland ports to Great Britain ports (Holyhead, Fishguard, Pembroke) are down 45 per cent — levels that are ringing alarm bells in Wales and among affected shipping lines.Â

Last week Nick McCullough, managing director of the ferry company DFDS Northern Ireland, told MPs on the Northern Ireland affairs select committee that in a low-margin business those kinds of drop-offs could not be sustained for long.

Of course, while shipping companies can move their ships (as Stena did) ports themselves cannot up sticks and chase the business.Â

Time will tell if this is a permanent shift, or if the teething problems can be dissipated to the extent that volumes across the “land bridge†will return to previous levels, but for now it seems as if Irish hauliers are voting with their feet.

[ad_2]

Source link