[ad_1]

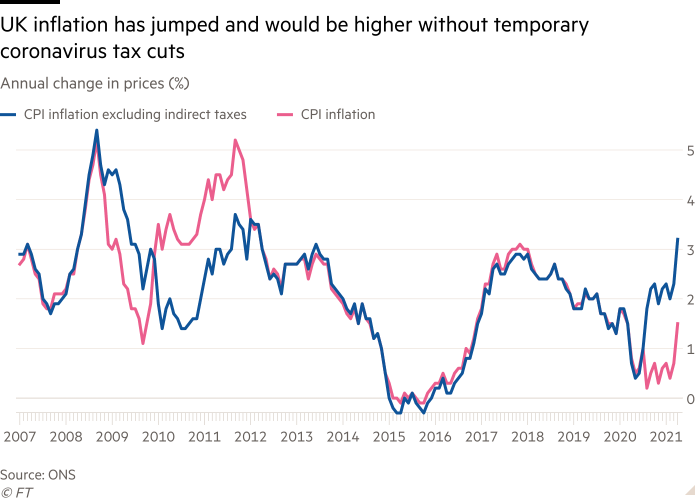

The annual rate of inflation in the UK more than doubled in April to 1.5 per cent on the back of higher petrol prices and gas and electricity bills, its highest level since the start of the coronavirus pandemic.

Rising from 0.7 per cent in March, the increase in the consumer price index matched expectations from economists and the Bank of England, who see the move as a step on the path towards inflation exceeding the 2 per cent target by the end of the year.

The official figures also showed that the rate of inflation was only kept as low as it was because of the temporary 5 per cent rate of value added tax on hospitality, which will last until the end of September.

If taxes were at their normal levels, inflation, measured by the consumer price index, would have risen to 3.2 per cent, the highest rate for nine years, if the tax increase was passed on to consumers.

Unlike in the US, where the headline inflation measure hit 4.2 per cent in April, most economists thought the UK figures did not yet show signs of a sustained overshoot in price rises, although some said there were some causes for concern in the data.

Prices of eating out in restaurants, staying in hotels, and clothing all increased sharply in April, after non-essential shops reopened and hospitality venues were allowed to serve customers outside.

Samuel Tombs, UK economist at consultancy Pantheon Macroeconomics, said the figures were not yet showing the worrying signs of a reopening surge in inflation seen in the US, but added that “CPI inflation will rise further over the coming months as prices for air travel, domestic accommodation and package holidays leap in response to rebounding consumer demandâ€.

Ruth Gregory, senior UK economist at consultancy Capital Economics, said that inflation would continue to rise in the months ahead, but any figures in excess of the BoE’s target would be temporary and the central bank was still on track to keep price rises under control. She said: “We doubt [inflation] will stay [above target] long, as energy-related effects go into reverse next year, reopening inflation eases and the stronger pound pushes down on inflation.â€

The core underlying rate of inflation, which excludes the volatile categories of energy bills, food, alcohol and tobacco rose from 1.1 per cent in March to 1.3 per cent in April.

Andrew Bailey, BoE governor, said on Tuesday that he was watching the data “extremely carefully†for evidence of a persistent overshoot in the bank’s target and would not hesitate to act by tightening monetary policy if risks became apparent.

Most economists said the April figures would not be sufficient to add to pressure on the central bank to begin raising interest rates from their historic low of 0.1 per cent.

But a vocal minority said the risks were mounting that higher inflation would prove more persistent in the short term and the longer term change in outlook also threatened to make this decade more inflationary than the last.

In a sign that there might be more inflation in the pipeline than the BoE expects, the costs of both raw material prices and goods leaving UK factories rose sharply in April.

The ONS said the input prices, covering goods such as oil and raw materials, were 9.9 per cent higher in April than a year earlier, up from a rate of 6.4 per cent in March and the highest reading on this element of the producer price index since February 2017.

George Buckley, chief UK economist at Nomura, said that with price indicators in business surveys beginning to flash warning signals and shortages of semiconductors, it “may only be a matter of time†before consumer prices rose more strongly.

“Don’t ignore the upside risks,†he said, warning that rises in factory gate prices had a “good relationship†with future inflation data, normally feeding through into consumer prices after about two months.

The headline rate of inflation of goods leaving UK factories rose to 3.9 per cent in April from 2.3 per cent in March, with sharp rises in the inflation rates of wood products, petroleum products and basic metals.

With the official house price index, produced by the ONS showing the fastest annual rise in prices since 2007 at 10.2 per cent in March, strong consumer demand as the economy opens from the pandemic lockdown has the potential to encourage companies to experiment with higher prices to raise margins after the Covid-19 shock.

Kallum Pickering, UK economist at Berenberg Bank, said while the April figures did not guarantee “a sudden bout of excess inflationâ€, strong spending by consumers this year and next was likely to “drive gains in demand beyond the pace at which businesses can add to supply via investment and hiringâ€.

For most advanced economies, the recent rise in inflation “marks a turning point . . . following more than a decade of disinflationâ€.

The ONS figures showed that house price increases were unevenly distributed, reflecting changing preferences as buyers sought more space during lockdown. The price of detached properties increased 11.7 per cent over the year, while those of flats and maisonettes increased by 5 per cent during the same period.

Growth in London was just 3.7 per cent, the lowest in the country and down from 4.4 per cent in February.

Additional reporting by Bethan Staton

[ad_2]

Source link