[ad_1]

It took Lily Andrassy two years after graduating in 2014 to land her dream job as a wardrobe assistant for the Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of Matilda. But since the first UK lockdown began in March 2020 she has been on furlough, picking up scraps of work as a seamstress and worrying about her future.

“I’ve got a degree. I’m highly qualified and experienced. I’m good at what I do . . . I’ve been working hard towards my career,†she said. But with her 30th birthday approaching in a few weeks, if she loses her foothold in a sector that is struggling to survive she would “have to start a new career from scratchâ€.

With luck — provided there is no further delay to the final easing of Covid-19 restrictions — Andrassy will be back at work in late August, preparing for Matilda to reopen. Although many people in theatre lost their jobs last year, in the uncertain months before furlough was extended the RSC kept her on and is ready to pay the contribution to her wages that will be required of employers from July, as the scheme begins to wind down.

This is exactly what the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme was meant to achieve: protecting jobs and incomes at the height of the pandemic but also, crucially, preserving links between skilled staff and employers, so that businesses could reopen quickly as restrictions lifted and workers could pick up their careers rather than being forced to make a fresh start.

At a cost of £64bn from its inception to mid-May — making it by far the biggest government intervention in the UK labour market for decades — it has largely succeeded in these aims.

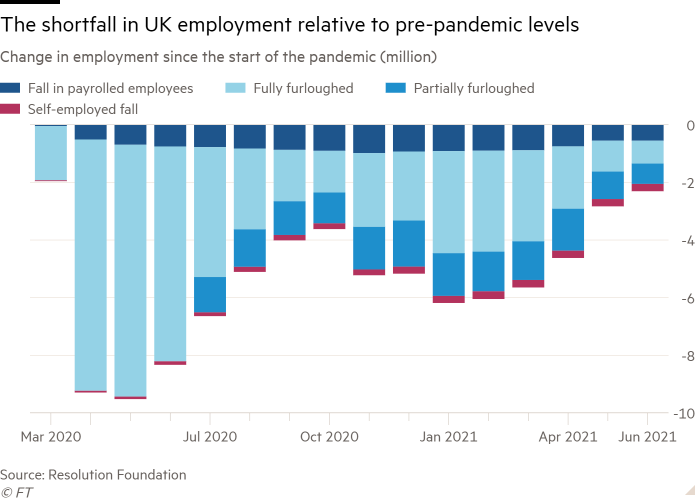

The number of jobs supported by wage subsidies fell from a peak of almost 9m in May 2020 to about 1.5m in early June 2021, according to Office for National Statistics data. By June, most were on partial furlough, meaning they were working at least some of their usual hours.

Meanwhile, hiring has surged and the Bank of England predicts unemployment, which stood at 4.7 per cent in the three months to April 2021, will rise only slightly as furlough is phased out, peaking at just under 5.5 per cent in the third quarter of 2021 — far lower than initially feared.

Yet there is still huge uncertainty over how solid the UK labour market will look when the prop of furlough is taken away. From July, furloughed staff will still receive 80 per cent of their usual wage, but employers will have to pay the first 10 per cent. This contribution will increase in August and the scheme will close at the end of September.

Some analysts think it should end sooner, arguing that furlough is now clogging up the jobs market, with hospitality employers finding people are reluctant to leave furlough for a new job that could fall through if cases rise again.

But Gregory Thwaites, a research director at the Resolution Foundation think-tank, said reports of worker shortages had been overplayed and the labour market was still far from fully recovered, with hiring bottlenecks being largely temporary.

“Everyone has to queue to get into the office after a fire alarm . . . that’s what’s happening in the labour market at the moment,†he said, adding that his estimates suggested vacancies were being filled faster than before the crisis.

The bigger worry is that most people who are still on furlough are clustered in sectors where activity is still severely restricted such as hospitality, arts, entertainment and tourism.

Kate Nicholls, chief executive of industry body UKHospitality, said about 200,000 people in the sector were still on full furlough, largely in businesses still unable to open such as events venues and nightclubs. In addition, up to a quarter of the hospitality workforce was still partially furloughed. If full reopening was delayed beyond July, tens of thousands of jobs would be at risk, she said.

Make UK, the manufacturers’ organisation, said use of the scheme was no longer widespread among its members, but that some, especially in aerospace, still relied on it to retain highly skilled staff.

While most large employers have now made the cuts they thought were necessary, with redundancy notifications back to pre-pandemic levels, many smaller companies have delayed making these difficult decisions.

“A lot of [travel] agents are very concerned about 30 September†when furlough closes, said Sue Foxall, managing director of Kinver Travel Centre, a small business based in Staffordshire. With virtually no income since the start of the pandemic, she has already let one member of staff go, but will keep two long-serving employees on furlough as long as possible in hopes of business recovering and because she cannot afford the redundancy payouts. But in September, “we have to take a big decisionâ€, she said.

“There is a lot of anxiety and worry about job insecurity,†said Emma Cross, chief executive of Citizens Advice in West Sussex, one of the areas where furlough has been heavily used because so many jobs are linked to Gatwick airport and related hospitality businesses.

The charity has seen more people seeking help because their employers plan to stop trading in July, as the companies are unable to afford either wage top-ups or redundancy payouts. Other businesses in similar straits have been switching people to zero-hours contracts to avoid liability, Cross said.

Yet while furlough’s end will undoubtedly trigger job losses, some believe these will be offset by the burst of hiring under way at businesses that are now growing.

“The goal should be to prevent unemployment, not to prevent job losses,†Thwaites said, adding that the jobless rate would not necessarily rise if flows into work continued at their current pace.

If the economy can reopen fully by September, the numbers still supported through the furlough scheme should have fallen to a point where it would “end with a whimper, not a bangâ€, said Tony Wilson at the Institute for Employment Studies. He added that it is “a policy we should all be really pleased to see the back ofâ€.

But if more bad news throws the government’s plans off track, Andrassy said that for her and many others the effects could be “catastrophicâ€.

[ad_2]

Source link