[ad_1]

The US equity risk premium, the extra return investors can expect for buying US stocks instead of risk-free government bonds, has fallen to its lowest levels of the past decade by some measures, as the fiery stock market rally stretches valuations.

Investment strategists have pointed to the indicator to justify a more cautious approach to US equities, which set a record high last week.

The equity risk premium for the S&P 500 index was “about as low as it can goâ€, Morgan Stanley analysts wrote in a recent note to clients, arguing that investors were not compensated sufficiently for the risk of owning equities rather than Treasuries.

The bank has recently downgraded small-caps and moved into more defensive, higher-quality stocks.

The nervousness was echoed by others on Wall Street. “I look at [the equity risk premium] now, and we are pretty much at the lowest level that we’ve been post the global financial crisis,†said Greg Boutle, head of US equity and derivative strategy at BNP Paribas. “It’s something that concerns me.â€

The focus on the equity risk premium marks the latest sign of how the sharp rally since the depths of the coronavirus crisis last March has made equities look expensive by several measures. The cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings, or Cape ratio, earlier this year pointed to equity valuations sitting at their highest in two decades.

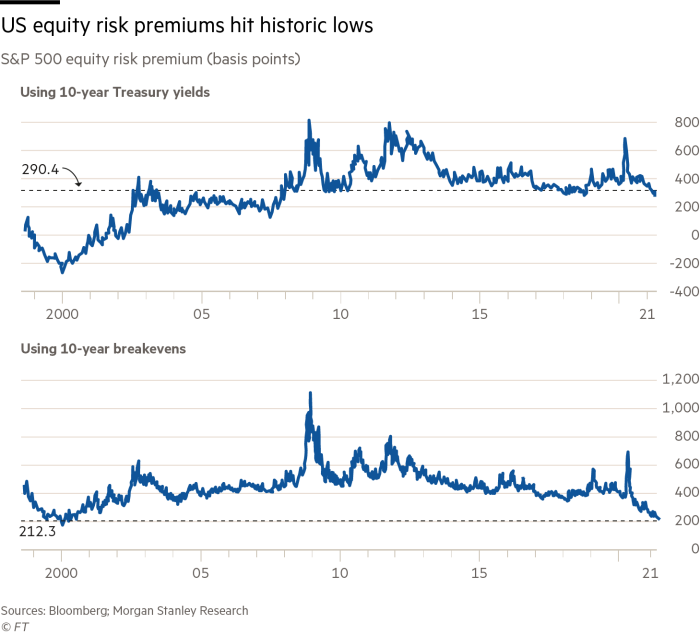

Morgan Stanley measured the US risk premium by comparing the “earnings yieldâ€, which compares expected profits with stock prices, with the yield provided by 10-year US government bonds.

Under that measure, the equity risk premium hovered around 2.9 percentage points as of last month, compared with 6.9 percentage points at the market’s bottom in March, and closer to 4 percentage points before the pandemic.

It is bumping up against the lowest levels of the past decade, but still higher than during the dotcom era or the run-up to the great financial crisis, when the premium was as low as -2.8 percentage points and 1.3 percentage points, respectively.

In a separate calculation, Morgan Stanley used inflation expectations, as measured by the 10-year break-even rate, to judge equity valuations, on the assumption that investors’ long-term hurdle for investing in stocks was to beat rising prices, not to earn minimal yield on Treasuries.

Under that calculation, the premium was just 2.1 percentage points — as low as it was two decades ago, during the dotcom bubble.

In the past year, US equity markets have rallied on the back of a swift economic reopening. While earnings expectations have risen at the same time, they were outpaced by the jump in stock prices, which rose so much that the earnings yield on the S&P 500 dropped from more than 5 per cent to 3.3 per cent in the past 12 months.

The yield on the benchmark 10-year US Treasury note, meanwhile, has climbed more than 1 percentage point, to 1.6 per cent, from its August bottom, as investors feared faster inflation.

Brett Nelson, an analyst at Goldman Sachs, said last month that an equity risk premium of 2.9 percentage points was still attractive and “light years away†from the “real bubble†in tech stocks of the 1990s.

“I wouldn’t necessarily take it as a warning sign,†said David Lefkowitz, an equity strategist at UBS. “If rates are rising because it’s even further conformation of an improving nominal growth outlook, I don’t think that would be too problematic.â€

Mike Wilson, chief US equity strategist at Morgan Stanley, sounded a more cautious note. “What are people going to be willing to pay for stocks? Nobody knows,†he said. “But they’re paying a very rich price.â€

[ad_2]

Source link