[ad_1]

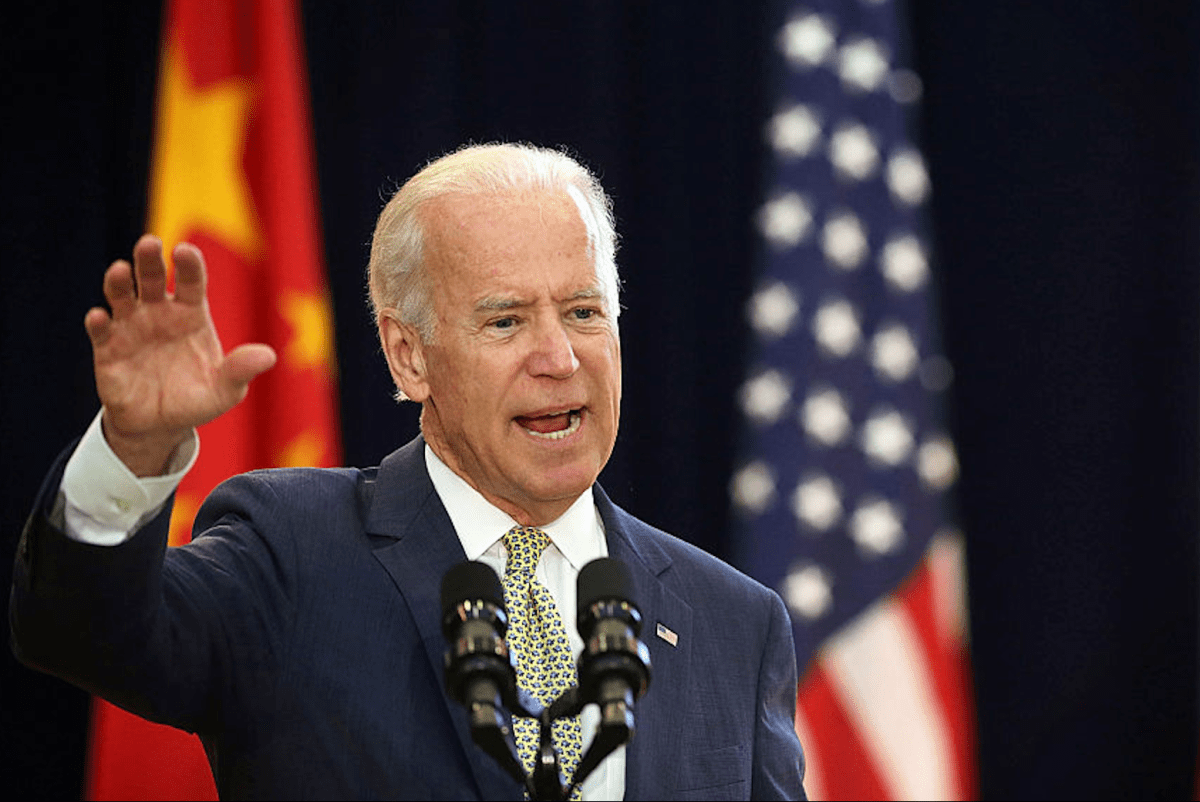

President Joe Biden’s first days in the White House have been highly consequential. With the decisive win and the political capital that put him in office, he is quickly moving to put the American ship of state back on the right course.

Reversing Trump’s initiatives

He has reversed some of the outrageous initiatives under Donald Trump such as withdrawing from the Paris Accord and World Health Organization as well as the Iran nuclear agreement, which Biden has yet to re-engage but is keen to do despite the objection of allies, namely Israel and Saudi Arabia, courted so closely by his predecessor.Â

While these are all positive developments, the fact that Biden can reverse these policies suggests that the next administration could do the same with his policies. What does that say about any agreement with the US? How can any country trust the US when any agreement can be reversed every four years?Â

Like no president in US history, Donald Trump used executive orders to change the status quo. Now Biden is doing the same, in reverse, with the stroke of a pen.Â

No change in attacks on China

To me as a Chinese-American focused on US-China relations, it seems that one thing that has not changed is China policy. Biden can’t possibly craft that policy all by himself. So who are those behind the scenes pulling the strings?

Some have held long-term negative attitudes toward China, such as the new Secretary of State Tony Blinken or Kurt Campbell, the new coordinator for Indo-Pacific affairs in the National Security Council. Others are totally clueless.

Right now any nominee for a position in the Biden administration has to pass a China-bashing litmus test even if the post has nothing to do with China. They all parrot the same old fake news: China is assertive, whatever that means, violates human rights – even using the term “genocide†to describe the supposed mistreatment of Uighurs – and took away Hong Kong’s rights.

Notice that, relatively speaking, the Tibetans are not mentioned as much. We all know that Xinjiang is the gateway to Eurasia and key to China’s Belt and Road Initiative. By contrast, Tibet is not that involved.

Even Myanmar’s leader Ann San Suu Kyi, the Nobel laureate courted by the West not too long ago, is now demonized over the so-called Rohingya crisis in Rakhine state. But this is just another part of the attempt to contain China. It is contributing to the construction of a deep seaport in Rakhine, which will allow China to import Mideastern oil without having to transit the Malacca Strait.

The following questions are pertinent. Does China want to replace the US as the world’s No 1 hegemon? Does China want to impose its political system on other nations through regime changes? Does China want to expand its borders to grab more territory from other nations, or to colonize other nations? Does China send out its military to force nations to do things they do not want to do?

The answers are no to all these questions. Yet no matter what China actually does, the US will try to demonize it.Â

Still trying to contain China

Graham Allison’s 2017 book Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’ Trap? suggests that clashes between the dominant power and the rising power often lead to war, as was the case between Germany and Britain a century ago.

In her capacity as director of policy planning in the US State Department under Trump, Kiron Skinner said in 2019 that the conflict between the Soviet Union and the US had been a family affair between two Caucasian nations, and that China was the first non-white nation to challenge the West. She thereby made it clear that she did not know her history.Â

Another Asian country, namely Japan, went to war against Russia in 1904 and against the US in 1941. It’s odd that this comment came from a black woman. What she foolishly said is in fact what white policymakers really think, but in today’s world would not or could not say.

In Fareed Zakaria’s December 2019 article “The New China Scare†in Foreign Affairs, he noted that on the economic front, almost every charge leveled at China today – forced technology transfers, unfair trade practices, limited access for foreign firms, regulatory favoritism for locals – was leveled at Japan in the 1980s and 1990s.

At the time (1988), Clyde Prestowitz’ influential book Trading Places: How America Is Surrendering Its Future to Japan and How to Win It Back explained that the United States had never imagined dealing with a country in which “industry and trade [would be] organized as part of an effort to achieve specific national goals.â€

Another widely read book of the era was titled The Coming War with Japan by George Friedman. But as Japanese growth tapered off, so did these exaggerated fears.Â

Will the fear of China taper off? I seriously doubt it.

[ad_2]

Source link