[ad_1]

Just hours after Jeremy Heywood and his wife Suzanne got the diagnosis of the lung cancer that ended his life less than 18 months later, the fire broke out in Grenfell Tower that was to kill 72 people.

That left Heywood, as UK cabinet secretary, having to cope the next day with Theresa May’s faltering response to that horror in west London — and with her continuing shock at losing her parliamentary majority the week before in a general election that she had chosen to call.

“The prime minister is still ashen-faced at the election result,†he told Suzanne. As she relates, “I nodded — our crises were unfolding in parallel, although I would have traded ours for Theresa May’s in an instant.â€

This is an astonishing book. Not for any political revelations, which may reflect the leaden hand of the Cabinet Office. Although the publishers say the government imposed no terms of publication, Suzanne Heywood gave officials a year to comment on the draft, and by many accounts they took full advantage of that generosity, peppering her with hundreds of questions and requests.

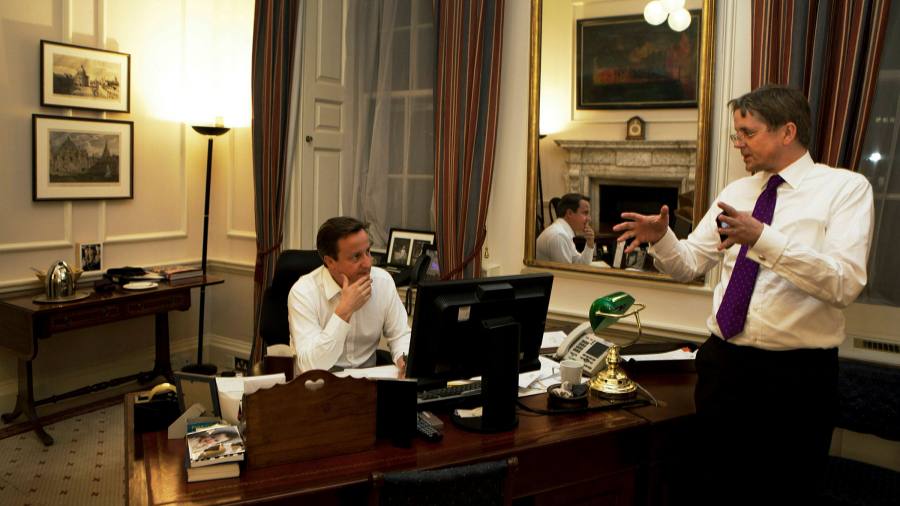

Still, in What Does Jeremy Think? she captures a remarkable sweep of recent UK political history and the central part that her late husband — a brilliant product and architect of the UK civil service and arguably the most influential cabinet secretary of modern times — played in making it work better.

Above all, she offers a reminder that the daily business of government is done by people: for all the talk about the “machinery of governmentâ€, the character of those people determines what happens.

Her chronicle, which she and Jeremy began after his diagnosis in June 2017 and which she augmented with interviews after he died in November 2018, starts with his role in the Treasury of the then Conservative chancellor Norman Lamont. That was also where they met; she was a bright fast-stream trainee undeterred in applying for a post working for Heywood, despite his reputation as “the scariest person in the buildingâ€.

The portrait adds fascinating nuance to well-known tales, such as how Tony Blair and Gordon Brown adroitly manoeuvred past each other before relations deteriorated into acrimony at the top of New Labour. Heywood was one of the few who could speak to both sides. The book is also rare for giving a generous account of Brown’s premiership, making clear how the financial crisis was his finest hour, although the voters did not thank him for it. It is interesting, too, how Heywood’s early scepticism about the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition gave way to an appreciation of the counterbalancing effect it had on each party.

There is a tendency to make Heywood seem always right (for instance, in thinking austerity policies too severe from the start). Writing some time after many events they describe, it would be hard for either Heywood to forswear the benefits of hindsight. But the account is accurate — understated even — about Jeremy Heywood’s unusual ability to broker compromise. That came out of his intellectual grasp of the issues and his striking empathy, which made him charming company — although he would not let a point rest in defence of the civil service he adored.

This is also a deeply human book. The author deftly weaves in her own high-colour story (a childhood on a sailboat; a PhD at the University of Cambridge; becoming a senior partner at McKinsey). Some of the most agonising passages are the couple’s five attempts at IVF, which did finally give them a son, followed by twins; some of the most recognisable, to working parents of young children, are the tussles about which one would be able to get to the office on time.

The loss of Heywood’s influence when illness finally forced him to step back in mid-2018 indisputably changed the course of events. I have lost track of the times people have said “that wouldn’t have happened with Jeremy thereâ€, from a run of London Evening Standard stories about Mark Carney’s departure from the Bank of England to the Johnson government’s prorogation of parliament or the desperate U-turns of coronavirus. Sir Mark Sedwill, Heywood’s immediate successor, was fluent in foreign affairs but never had the same backing from permanent secretaries nor the grasp of the Treasury.

One lasting question is whether Heywood was too good. His skill in pursuing a middle way arguably let May believe that a Brexit compromise existed between what the EU would accept and the UK parliament would back. It didn’t. Had someone said, “No, prime minister†forcefully after the 2017 election, it is possible that the country would have been spared her the battles with parliament and own party that finally brought her down. “Too goodâ€, though, is not a criticism made often of government. There is no question about how much Heywood has been missed.

What Does Jeremy Think? Jeremy Heywood and the Making of Modern Britain, by Suzanne Heywood, William Collins, RRP£25, 556 pages

Bronwen Maddox is director of the Institute for Government, a UK think-tank

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café.

Listen to our podcast Culture Call, where FT editors and special guests discuss life and art in the time of coronavirus

[ad_2]

Source link