[ad_1]

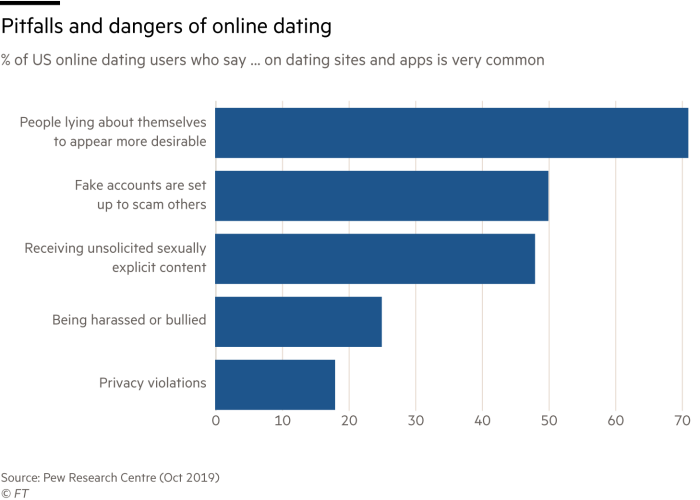

The problem with dating apps is that nobody seems to like them very much and yet nobody is sure how else to find a date. Most of us know someone who met their partner online and is blissfully happy. But here is a more depressing statistic: only a tenth of dating app users in the US have found a committed relationship, according to Pew research. More than half of young women have experienced some form of harassment.

Over the past decade, free mobile dating apps such as Tinder have colonised the search for love, convincing millions of people to sign up and swipe right in their quest for a partner. Meeting complete strangers for near-blind dates is no longer out of the ordinary. Yet the digital disruption of the most personal aspect of our lives has not increased the odds of finding happiness. The world has never been more connected, or more alone. This apparent contradiction is the subject of two new books that chart the highs and lows of online dating.

American journalist Nancy Jo Sales is clear about who to blame for the modern dating malaise: tech companies. In Nothing Personal, she recounts how, at the age of 49, she signed up to Tinder following a break-up and was initiated into a world of creepy messages, unsolicited sexual photos and ghosting. Although she met a number of men and formed a longstanding relationship with the charmingly inconsistent Abel, the experience is often “exhausting†and “a shamâ€. The app is a “dehumanising haystack†of faces.

In lockdown, Sales hoped that there might be a return to conversational courtship only to find that “nothing much has changed in the dystopian world of online datingâ€. Not only that but the apps seem to have put an end to the possibility of meeting a partner in the real world. “The tech industry’s colonization of dating had changed human behaviour so quickly, it seemed we were already losing the ability to connect on our own, to court and spark,†she writes.

Sales went viral for a 2015 Vanity Fair story on dating apps and hookup culture, one of the first to describe the brave new world of dating as dysfunctional. A global “techlash†in the years since then means that the idea of Silicon Valley companies as a danger to society is no longer novel. But the combination of Sales’s long-term interest and her personal experiences mean she is still able to offer original, thoughtful insights.

The result of tech’s conquest of dating, she says, is loneliness. Over half of all adults under the age of 35 in the US say they do not have a steady romantic partner, the lowest figure since data was first collected in the 1980s.

Compare this to the financial success of the companies behind the apps. Tinder is part of Match Group, which has 44 other dating platforms including Hinge and OkCupid. Last year it reported revenue of close to $2.5bn.

The goal of dating apps, of course, is not to help users fall in love but to make money by collecting their data and subscriptions. Constant swiping through face after face with little other context is designed to be addictive. Sales quotes a chilling blog post by OkCupid founder Christian Rudder titled “We Experiment On Human Beings!†She also traces the bro-culture origins of some of the app’s founders, including the co-founder of Match.com who secured the rights to the domain name for one of the world’s biggest porn sites.

Sales is no prude. She joins Tinder looking for both relationships and fleeting encounters. But she finds that many of the men she matches with believe the relative anonymity of online life gives them tacit permission to behave poorly. Her thesis is that dating apps are particularly bad for women. Many of the men she talks to seem wedded to a double standard that dating apps facilitate flings but that the women who engage in them deserve little respect. Perhaps, she writes, the prevalence of harassment will lead women to wonder why they have made more strides in the public arena than the private one.

Sales, a journalist at Vanity Fair whose article “The Suspects Wore Louboutins†was made into the Sofia Coppola-directed film The Bling Ring, knows how to weave deep reporting into personal stories. Nothing Personal is both a memoir of her own romantic adventures and the rise of what she calls Big Dating.

She is so good at making the reader feel like a confidant that I doubt I will be the only one to wish they could reach in and stop her from being so polite to bad-mannered dates and to take less risks. She seems to believe that certain things — inviting strangers over to her house and eschewing safe sex — are simply part of the new online hookup culture. This is not true.

The idea that the internet is a foreign land that allows people to act in ways they would never otherwise contemplate feels old fashioned. The division between the internet and the real world collapsed a long time ago.Â

At the opposite end of the spectrum sits Laura Friedman Williams, whose book Available chronicles a joyful dive into the dating pool at the age of 46 after the end of a long marriage. There has been a rash of post-marriage, joy of dating app books, including British journalist Rosie Green’s How to Heal a Broken Heart and podcast host Helen Thorn’s Get Divorced, Be Happy. All tend to follow the same arc: a long-term marriage ends, bringing heartbreak and insecurity. Then comes the miraculous discovery that dating and being unshackled from wifely duties is far more fun and interesting than being married.

Williams is an amiable companion on the dating circuit, although she describes herself as someone whose previous writing credits consisted only of “countless PTA newslettersâ€. Before having children, however, she worked in book publishing. This means she was probably aware that explicit memoirs by women often find an enthusiastic audience. Thus the graphic stories of one-night stands and Brazilian waxes.

FT Weekend Festival

The festival is back and in person at Kenwood House (and online) on September 4 with our usual eclectic line-up of speakers and subjects. Infusing it all will be the spirit of reawakening and the possibility of reimagining the world after the pandemic. To book tickets, visit here

Sales offers a more thoughtful analysis of the ways in which dating apps encourage people to promote themselves as if they were their own product, an impulse that other social media platforms also exploit. She is right that users are not thinking carefully enough about the sensitive information they share either, information that can be used by companies.

If you are newly single and considering signing up to a dating app then read Williams. If you have been on the apps for a while and wonder why you’re having a hard time read Sales. Dating apps mean that it has never been easier to meet new people but they also appear to have bred a culture of harassment and disrespect. While contemplating another bad date, Sales quotes French philosopher Paul Virilio who wrote: “When you invent the ship you also invent the shipwreck.†Dating apps have changed the search for love, but not necessarily for the better.

Nothing Personal: My Secret Life in the Dating App Inferno by Nancy Jo Sales, Hachette Books £28/$14.99, 384 pages

Available: A Memoir of Sex and Dating After a Marriage Ends by Laura Friedman Williams, The Borough Press £14.99/$12.99, 400 pages

Elaine Moore is deputy editor of Lex

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café

[ad_2]

Source link