[ad_1]

Sir Isaac Newton was a giant of science and, for many years, Master of the Royal Mint. But neither mathematical brilliance nor financial experience saved him from investment disaster.

A wealthy man by contemporary standards, Newton had by 1720 accumulated £19,000 worth of UK government bonds, and 10,000 shares in an enterprise called the South Sea Company, which had been granted a monopoly on British trade with South America, including in slaves.

War with Spain had long stymied the company’s fortunes, but that did not prevent its stock from soaring. Acting perhaps with the wisdom of his years, a 67-year-old Newton in the spring of 1720 sold his South Sea stock for a tidy profit of £20,000.

But then the madness gripped him. As South Sea shares just kept on rising, Newton reversed course and ploughed his proceeds back in. He doubled down, converting his government bonds into even more South Sea Company stock.

Unfortunately, the bubble burst in the autumn of 1720, wiping out the ageing Newton’s savings. The scientist subsequently forbade anyone ever uttering the words “South Sea†in his presence, and famously griped that he “could calculate the motions of the heavenly bodies, but not the madness of peopleâ€.Â

Newton’s misfortune shows that anyone can be swept up by a mania — an apt historical lesson at a time when many stock markets around the world are punching through new record highs despite the long shadow cast by the coronavirus pandemic.

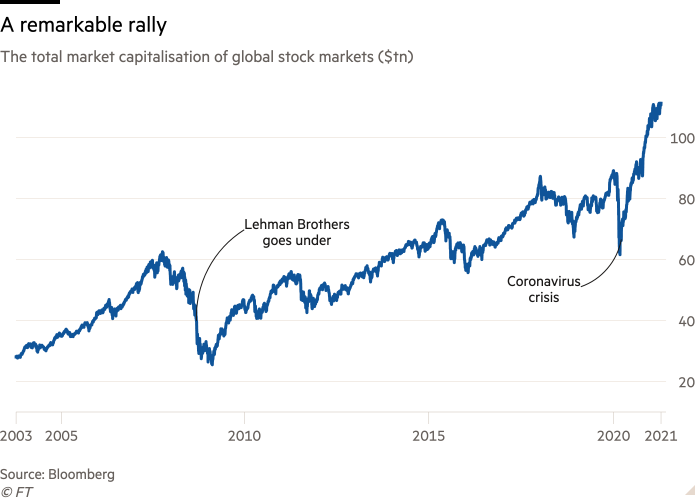

All told, the global equity market has now climbed over 80 per cent from its March 2020 nadir — adding a remarkable $50tn of value in just over a year.

Yet many market veterans are growing perturbed at the myriad signs of euphoria, classic harbingers of a stock market rally on its final legs.Â

“The long, long bull market since 2009 has finally matured into a fully fledged epic bubble,†Jeremy Grantham, the venerable British value investor, wrote earlier this year in a letter to clients of GMO, the money manager he co-founded in 1977. “Featuring extreme overvaluation, explosive price increases, frenzied issuance, and hysterically speculative investor behaviour, I believe this event will be recorded as one of the great bubbles of financial history, right along with the South Sea bubble, 1929, and 2000.â€

Is the proverbial casino about to burn down again? And if so, is this the time when ordinary investors should be quietly tiptoeing out of the smoke-filled hall — before the building catches fire and they are trampled by the finance industry’s big-rollers scrambling for the exit?

Looming leverage

The Archegos affair illustrates the dangers lurking in markets today. On March 26, the US stock market was abruptly pummelled by a series of mysterious, whale-sized trades. Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley — two Wall Street powerhouses — were dumping multibillion-dollar gobs of stock in companies like Viacom and Discovery, the media companies.

Quickly, it emerged that the $50bn fire sale involved the assets of Archegos Capital Management, an opaque investment firm run by former hedge fund manager Bill Hwang.

Hwang had in 2012 been forced to shut down his hedge fund after getting fined for insider trading. But he dusted himself off and started aggressively trading with his own money. Taking advantage of the market rally that followed the coronavirus crash in March 2020, he quietly built a substantial personal fortune, worth roughly $20bn at its peak.

But his bets were built on borrowed money. When Hwang was in late March unable to offer his bankers enough collateral, they were forced to liquidate everything in a hurry. Some banks moved quickly enough to avoid major hits; others swallowed humiliating, multibillion-dollar losses.Â

The scale and speed of Hwang’s rise and fall are unprecedented. Yet some analysts and investors fret that his debacle is no one-off but is symptomatic of a broader and subtle danger to financial markets: leverage.

Leverage is often used as a synonym for debt, for example the loans that a hedge fund might get from a bank or a margin account that a day-trader might obtain from their brokerage. The idea is to juice the returns — at the risk of magnifying the losses if the bets go wrong. International data is sparse, but US margin debt spiked to a record $822bn in March.

Leverage is also the term used for the extra fuel one can spritz on a wager through derivatives such as options or swaps — the latter were Hwang’s choice of poison. HSBC bond analyst Steven Major, for one, worries that the Archegos affair signals that excessive leverage is a mounting risk.Â

“For all the best laid plans there are shocks we fail to forecast and feedback loops that we cannot fully understand until after they happen,†he observed in a recent report. “When leverage is the underlying explanation behind what appears to be a series of individual episodes in financial markets — the latest being Archegos — the narrative will probably evolve from idiosyncratic to systemic risks.â€

At the same time, there has been a surge of stock market interest from people cooped up inside by pandemic lockdowns. The US has been the epicentre for a retail trading earthquake — ordinary Americans now account for almost as much trading as all hedge funds and mutual funds combined.

But this has turned into a global phenomenon, and the UK too has seen a trading boom. The drivers, as elsewhere, are mostly younger people keener on excitement than building a retirement nest egg, and therefore seeking racier bets rather than stolid investments.

Many have rushed on to online investment platforms, which allow ordinary investors much easier access than the old tools of the telephone and the cheque book. The rise of the online, commission-free US brokerage Robinhood encapsulates this trend — one of many apps that have transformed trading into more of a game.

Hargreaves Lansdown, the UK brokerage, reported in February that its net new business spiked 40 per cent to £3.2bn in the final six months of 2020, when it added 84,000 users — most of them much younger than its average customer. Rivals AJ Bell, IG Group and CMC Markets have all also reported chunky, profit-boosting jumps in the number and activity of customers over the past year.

Robert Buckland, chief global equity strategist at Citigroup, emphasises that the UK retail trading boom remains a shadow of that seen in the late 1990s, or witnessed in some other markets today. But he notes how attitudes everywhere seem to have subtly shifted, from investing to more speculative trading. “People have lost touch with the fact that shares represent a little bit of a company,†he argues.Â

The retail frenzy might have been easier to shrug off if it weren’t for the fact that many corners of the global stock market are now trading at punchy levels. The combination of investor euphoria, leverage and lofty prices has proven a toxic mix many times in the past, from Newton’s South Sea bubble to more modern stock market debacles.Â

Take a popular valuation metric designed by Nobel laureate economics professor Robert Shiller that compares US stock prices to the average inflation-adjusted corporate profits over a rolling 10-year period, and is therefore a decent measure of longer-term shifts in valuations. The Shiller ratio currently stands at 37.2 times, up from 26 times a year ago and a level only exceeded at the peak of the dotcom bubble. Other markets are less extreme, but virtually every major bourse is looking pricey, notes Maya Bhandari, a fund manager at Columbia Threadneedle. “Market valuations are pretty full wherever you look,†she says.

In another sign of euphoria, equity funds globally have attracted $569bn in the past five months. That is more than the past 12 years combined, Bank of America notes. There has even been an eerie echo of the South Sea Bubble in the recent Spac boom — “special purpose acquisition companies†that are essentially just listed cash shells for financiers to use to buy other companies.

Perhaps the wildest example of pure froth is dogecoin, a meme-based crypto asset started entirely as a joke. The overall value of its “coins†earlier this month spiked to a high of over $50bn, making it more valuable than carmaker Ford or hotel operator Marriott.Â

The much bigger bitcoin market is now worth over $1tn, more than all listed US banks combined, and when Coinbase, a crypto exchange, floated in mid-April it was valued at $76bn, nearly three times the value of Nasdaq, the once-upstart exchange that it listed on.

“It’s very difficult not to be nervous,†admits Richard Buxton, a veteran UK equity manager at Jupiter Asset Management. “It’s classic stuff that after a correction we’ll look back and say the signs were all there.â€

That said, investment managers and analysts stress that it is also difficult to be too gloomy about the stock market outlook. The whiff of ebullience is unsettling, but many struggle to see what could deflate the mood.Â

The global economy is expected to enjoy its biggest boom in generations in 2021-22. While millions of poorer people have lost their jobs and spent their savings, many better-off people in the wealthier world have been shielded from the financial impact. They will soon emerge from lockdowns inoculated, flush with savings and desperate for something other than Netflix and Zoom calls.

Fiscal and monetary stimulus since Covid-19 emerged now totals about $20tn, according to JPMorgan Asset Management. With central banks promising to keep interest rates pinned near zero — or in some cases below that — for years to come, bond yields are likely to remain subdued, leaving equities as pretty much the only viable way for savers to generate above-inflation returns.Â

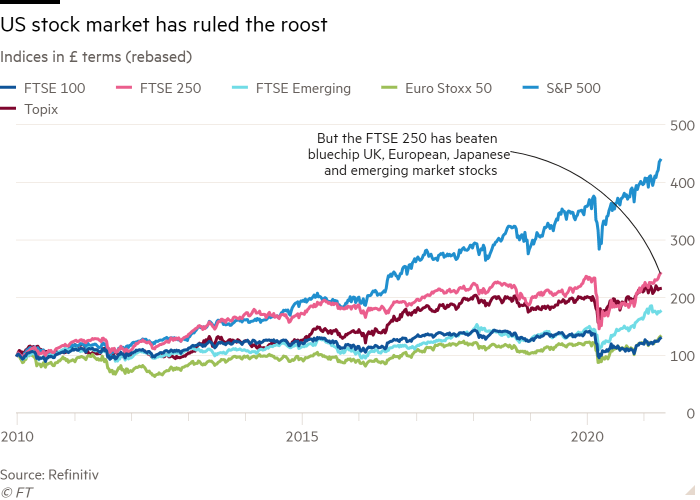

UK investors have an unusual vantage point over all the euphoria, because the blue-chip FTSE 100 index still trades well below its peak, and UK stocks have long been held back by the UK’s poor economic performance and Brexit. As a result the UK stock market now actually looks more attractive than most other markets, some fund managers say.

The FTSE 100 index trades at just 14.5 times the expected 12-month earnings of its members. In contrast, the Euro Stoxx 50 of continental corporate heavyweights trades with a price-to-earnings ratio of almost 17 times, and America’s S&P 500 at an even punchier 21 times.Â

“Frothy is not the word I associate with the UK market,†observes Laura Foll, a fund manager at Janus Henderson. “I don’t see any signs of irrational exuberance outside of a few small, isolated pockets. By almost every metric the UK equity market still trades at a discount to other markets.â€Â

This is partly explained by the UK’s lack of glamorous technology stocks. But even when one adjusts for the different sectoral make-up of indices, the UK looks like an outlier, according to Foll. Bank of America’s survey of global investors indicates that a majority have been underweight the UK equity market for most of the past two decades, and Brexit has only deepened the aversion.Â

Many international investors have written off the UK until there is clarity on the long-term economic impact of the country’s acrimonious EU exit, according to James Illsley, a fund manager at JPMorgan Asset Management. “There is a hangover of Brexit worries, where global investors just exited the UK because they thought ‘why take the risk if you didn’t have to’.â€

This might prove wrong, given the economic benefits the UK is likely to reap from its successful vaccine rollout, even though Brexit will remain a headwind. Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates, a big US money manager, recently argued that UK equities may be the “trade of the decadeâ€.

The FTSE 250 index of midsized, more domestically-orientated companies looks particularly attractive at the moment, despite the gauge performing as well as the US stock market over the past two decades. “We’ve had this seam of gold in the UK market, even while everyone has just moaned about the FTSE 100, the poor UK economy and Brexit,†says Buckland.Â

Stay the course

Of course, just because UK stocks are cheaper than most other major markets, doesn’t mean that they can’t stay cheap or become even cheaper. Nor will lower valuations help much should global markets suffer another tizzy — UK equities took a harder beating than US ones when Covid-19 first rattled markets.Â

Still, the adventurous investors might want to bet on the UK stock market regaining its mojo in the coming years, or that the renaissance in beaten-up “value stocks†— often found in industries and sectors left for dead in the pandemic — will continue to gather momentum. Value stocks globally have gained 27 per cent since several Covid-19 vaccines emerged in early November, nearly twice the gains of more glamorous “growth†stocks, but many analysts think they have further to run.

Nonetheless, the reality is that for most people, investing is fortunately one of the few arenas in life where it actually pays to be a little bit lazy. Countless studies have shown that trying to time markets is a foolish endeavour, with even professional investors often hurting themselves by opportunistically flitting in and out of markets. “Trying to time the market is a death knell,†says Buxton.

Simply saving in a boring, diversified portfolio of securities — and utterly ignoring day-to-day and year-to-year financial market fluctuations — has historically been a long-term winning strategy. Luckily, it is now easier and cheaper than ever to assemble a broad bunch of global stocks and bonds through plain-vanilla index funds, which the data shows beats the vast majority of active fund managers in the long run.Â

Warren Buffett has observed that smart investing is like dieting — not complicated, but not easy either, due to the quirks of human nature.

“Owners of stocks . . . too often let the capricious and often irrational behaviour of their fellow owners cause them to behave irrationally as well,†the ‘Oracle of Omaha’ once observed. “Because there is so much chatter about markets, the economy, interest rates, price behaviour of stocks, etc, some investors believe it is important to listen to pundits — and worse yet, important to consider acting upon their comments.â€

Boring index funds were not around in Newton’s day. But had he simply invested in a UK one when he became Master of the Royal Mint in 1699, it appears his returns would have been tenfold by the time he passed away in 1727 — despite the epic bout of wealth destruction wrought by the South Sea Bubble.Â

The author is the FT’s global finance correspondent

[ad_2]

Source link