[ad_1]

Britain’s steel industry is never far from a crisis. In recent months, the woes plaguing Liberty Steel and its controversial owner Sanjeev Gupta have captured the headlines.

But the sector faces a much bigger and more existential threat than uncertainty over Gupta and the future of Liberty Steel: how to “green†steelmaking.

Britain’s commitment to reaching net-zero emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050 has raised the stakes for the industry and the 33,000 people it employs.

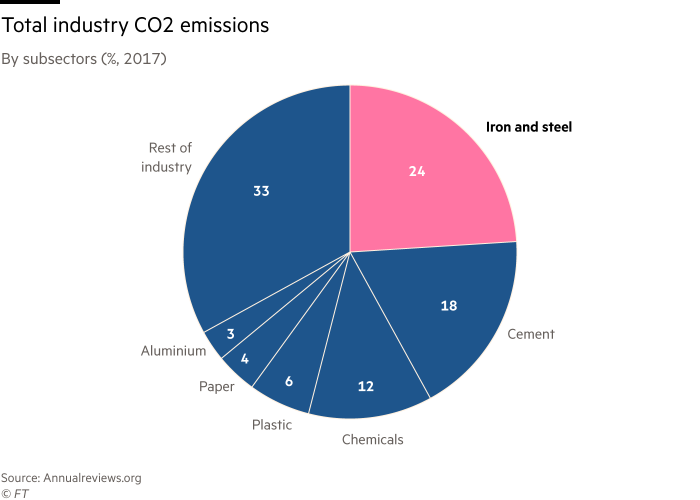

In the UK, steel is the biggest industrial emitter of carbon dioxide. The Climate Change Committee, the government’s independent advisory group, has suggested steel production needs to be “near-zero†emissions by 2035 — a hugely ambitious target.

Ministers have stressed the strategic importance of the industry’s role in post-Brexit Britain, but concern is growing among some executives that a comprehensive strategy to secure its future and put it on a sustainable footing is still missing.Â

Domestic producers have for years struggled to stay competitive against lower-cost international competition and global oversupply.

Now they face the additional burden of cleaning up their emissions. The potential costs are eye-watering and cannot be met by industry alone.Â

Chris McDonald at the Materials Processing Institute, a steel research group, estimated that to make green steel a reality would require £6bn-£7bn of investment on sites themselves, on top of supporting infrastructure.Â

“Where is the money going to come from? That’s the tough question,†he said.

Industry executives declined to comment publicly but insisted their companies are committed to change. They stressed, however, they would only make investment decisions based on a clear strategy by the government. The industry hopes to present its own detailed proposals to ministers in the autumn.

“There is a window of opportunity now,†said one UK industry executive. “The UK wants to be in the vanguard of decarbonisation, but we need clarity on the direction of travel.â€

A second executive said: “Ministers need to give a sense of how they will make it competitive to invest.â€Â

Speaking to MPs at the end of May, business secretary Kwasi Kwarteng insisted that there was a “strategic case for UK-produced steelâ€. Government support, however, had to be “allied with a commitment to decarbonise by the industryâ€, he added.

Concern is growing that without a clear road map some of Britain’s producers, most of which are owned by international groups, will hold off investing before it is too late.Â

Analysts point out that Jingye Group, the Chinese company that took over British Steel in November 2019, promised to invest £1.2bn over a decade into upgrading facilities, but has so far unveiled plans for only £100m.

BEIS, the UK business department, said it was “working closely†with the steel sector to support its transition to a low-carbon future.

It said its new Industrial Decarbonisation Strategy, published in March, committed the government to consider the implications for the sector.

Officials also stress that the government has launched a number of initiatives, including a £315m Industrial Transformation Fund to support businesses with high energy use to cut their bills and a £250m Clean Steel Fund to help companies switch to low-carbon steel production, although the latter will not start disbursing funds until 2023.

The government is also consulting on new procurement rules that could benefit domestic producers. The merits of a carbon border tax are also being debated.

The industry, however, says the right policy framework is still missing.

Gareth Stace, director-general of trade body UK Steel, said that Boris Johnson’s government was “more engaged†with the sector than previous ones and welcomed the decision by Kwarteng to reform the UK Steel Council this year.

However, none of the initiatives announced so far “add up to a comprehensive strategyâ€, he added.

Help on reducing electricity costs in particular was vital, he said, because all decarbonisation options for steel would involve a huge increase in electricity consumption.

More than 80 per cent of UK steel is made in carbon-intensive blast furnaces, mainly those of its two largest players — British Steel’s operations at Scunthorpe and at Tata’s steelworks at Port Talbot in Wales. Both companies will have to decide soon whether to invest in their current facilities or switch technology completely.

Another option would be to invest in new electric arc furnaces. These melt down scrap, rather than converting raw materials, and emit a fraction of the CO2 of blast furnaces.

Gupta’s steelworks at Rotherham in South Yorkshire are among those in the UK that already use electric arc furnaces.

Steel produced in an electric arc furnace could be close to zero carbon if powered with electricity from renewables, but the steel cannot be used for some important applications and there is concern in some quarters that Britain would lose its primary steelmaking capacity.Â

Expanding the use of electric arc furnaces would also require ensuring more scrap remains in the country and is not exported.

Executives say much hinges on the government’s plans to promote the use of hydrogen in steelmaking and support to develop the necessary infrastructure — investments that are beyond the reach of single companies.

A recent report by the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit warned the UK was falling behind Europe in the development of clean steel. The report said 23 hydrogen steel projects are either planned or under way across Europe.Â

It pointed out that underpinning some of the bloc’s most ambitious steel projects was Germany’s hydrogen strategy, which is backed by €9bn in funding and aims to develop the use of hydrogen from renewable energy.Â

There is another, more sensitive question, that ministers will have to tackle: how to manage a “just transitionâ€. If the production of steel becomes more efficient and more productive as it becomes more “greenâ€, that will inevitably lead to job losses.

“There is a responsibility here that goes beyond the industry,†said McDonald at the Materials Processing Institute.

Asked by MPs to sum up the sentiment of Britain’s steelworkers at a recent evidence session, Roy Rickhuss, general secretary of the Community trade union, said: “We understand the need of net zero . . . nobody from the trade union side is burying their head in the sand. We want to see a fair and just transition.

“There is a lot of uncertainty. A lot of concern and a lot of worried steel workers. It’s not just Liberty . . . we all want to know what the plan is.â€

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

Â

[ad_2]

Source link