[ad_1]

Soon after the first Olympic tie-in campaigns finally began to show up in Japan’s primetime television slots in early summer, the advertising giant Dentsu told investors to expect a huge $800m profit windfall.

Unfortunately for the company — historically considered among the most powerful in Japan — the good news had nothing to do with its core business, its growth prospects, or the delayed Tokyo 2020 games in which it has been so centrally involved.Â

Instead, the profits came from the $3bn sale of Dentsu’s headquarters building in Tokyo: a 48-storey, teardrop-shaped architectural icon that befits the company’s outsized share of Japan’s $55bn advertising market.

The sale of the skyscraper may rank as Japan’s biggest ever single-building transaction, according to analysts, bankers and long-term Dentsu clients. But it also masks internal torment at a company whose problems may have finally outweighed its swagger.

“As with the sale of its headquarters, the company is in a phase where it is shamelessly shrinking its balance sheet to generate cash to invest in future growth,†Citigroup analyst Hiroki Kondo said. “There is a real sense of crisis at Dentsu.â€Â

According to one former Dentsu executive, this mighty but conservative group is struggling to adapt to changing times, to the digital revolution in advertising and to a domestic market where it still has a 28 per cent share but that is increasingly different from the one it has dominated for more than a century.Â

At the same time, the Tokyo Olympics, which were supposed to bring in revenues to buy the company time to address its shortcomings, have become a heavy drag on management resources.

Sponsors signed up by Dentsu have even brought in outside expertise to assess the potential damage of continuing to trust the company with their campaigns and of remaining prominently associated with an event that experts warn could produce a medical disaster.

“Dentsu is retrenching in the Asia region [as management diverts to the Olympics], and for the last six months it has been losing both old clients and pitches for new business. Clients need advertisers to be transparent and innovative, and when they look at Dentsu, they are not seeing that, they see a company behind the curve,†said one former executive.

Dentsu responded that it was “strongly positionedâ€, noting that its first-quarter overseas media advertising fees doubled from a year earlier as a result of expanding fees from existing clients and acquiring new ones.

Before the pandemic and before the postponement of the Olympics, Dentsu’s problems appeared serious, but more solvable. In 2016, the company was caught overcharging clients, including Toyota, for online advertising. Later that year, the suicide of a graduate recruit was officially designated as “death by overwork†and forced the resignation of the company’s president.Â

French investigators have, for six years, been probing the background of Tokyo’s successful bid to host the Olympics in 2020. Their allegations include that sizeable funds were funnelled from the bid committee to people deemed able to sway the outcome of the vote through companies and individuals that had historic contacts with Dentsu. One former senior Dentsu executive, who denied improper behaviour, told Reuters he distributed gifts and helped secure the support of a former Olympics powerbroker suspected by French prosecutors of taking bribes. Dentsu has denied any involvement in the matters subject to the French probe.

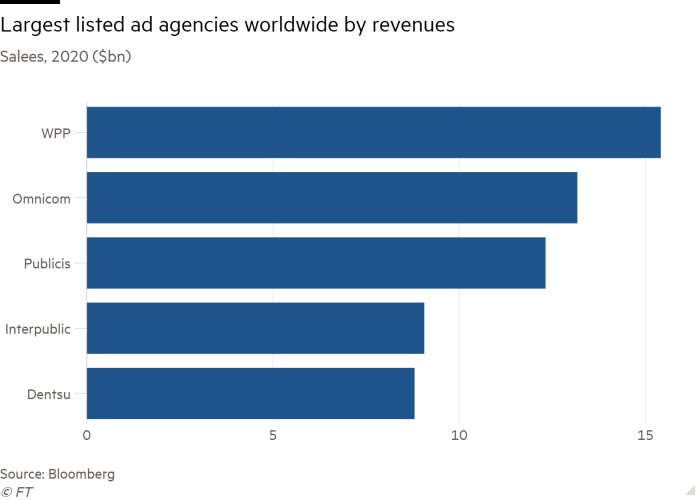

But the Olympics were also a critical profit source for the world’s fifth largest advertising agency and a symbol of its continuing dominance at home. Dentsu was brought in soon after Tokyo won the Olympic bid and was able to talk more than 40 Japanese companies into becoming sponsors and performing a “national duty†by doing so. The result was the most heavily sponsored event in history, a record $3.1bn financed mostly by Japanese corporations paying, in some cases, $100m each.

But while that was beneficial to Dentsu, the real prize would have come in the run-up to and during the games, in the form of campaigns run by the various sponsors and what should have been frenzied competition for the best TV advertising slots, most of which Dentsu controls. Citigroup analysts estimated all this would have contributed about ¥10bn ($90m), or 9 per cent, to the group’s annual operating profits.

But that rosy scenario has now faded, as corporate sponsors have held back from Olympic TV adverts fearing reputational damage from association with an event that faces public opposition.Â

“The real danger is of course in what perception the Olympics gets — at the moment there is an idea that it could maybe happen without a disaster, but the risks are extremely high,†a company close to Dentsu said.Â

If the Olympics ends without a spike in Covid-19 infections, Dentsu may be able to recoup some revenues through adverts capturing post-games euphoria. But even then, Kondo estimates that the company will at best generate no gain from an event that it has a four-decade relationship with and that a former executive says is part of the company’s “raison d’êtreâ€.

Analysts and industry executives say the longer-term fallout could be that Dentsu is forced to mend ties with companies disgruntled by the meagre marketing benefits of their Olympic sponsorship by offering discounts on advertising slots.Â

“That is going to hurt Dentsu quite a bit, because they had been banking on all the campaigns and the TV advertising that was going to come out of the Olympics — not the original sponsorship deals but all the work those deals would ultimately guarantee them,†the person close to Dentsu said.Â

The games aside, the pandemic has also caused big problems. The downturn in global advertising spending resulted in a large writedown in goodwill from its £3.2bn takeover of the UK’s Aegis in 2013 and the frantic buying of nearly 200 firms since then, which resulted in a record loss of $1.4bn last year.

“There was a spree of acquisitions by Dentsu . . . The problem was that they couldn’t integrate them,†the former Dentsu executive said.

The group is also aggressively cutting costs, particularly in Japan, to try to make itself nimbler and a better fit for the digital era. While it now generates more than half of its gross profits from digital ads and related consulting services, industry executives say its dominance in traditional media resulted in a slower digital transition compared with non-Japanese rivals.

The sale of the headquarters, said people familiar with details of the deal, is a sign of the turmoil at the top.

Potential buyers said they had quickly decided against it, partly because making space for new tenants would be costly as the building was tailor-made for Dentsu.

One section of Dentsu management held discussions with a financial group that was not the company’s main bank over selling the building to Japanese real estate group Kenedix, according to people familiar with the deal.

A second group moved to block that, inviting another domestic property giant Hulic to bid. Hulic was successful, said people familiar with the deal, largely because it was offered cheap financing by Dentsu’s main bank Mizuho.

The company declined to comment on the building’s buyer but said the sale was part of its years-long effort to implement remote work and other flexible work practises, not a result of its financial performance.

Dentsu executives say they will use the newly acquired cash from asset sales for acquisitions, but analysts remain sceptical of the company’s growth potential both at home and overseas beyond the immediate boost in profit margins from the cost cuts.

“We think restructuring could have a negative impact near term, including lower new project acquisition, and expect it will take time for these initiatives to contribute to top-line growth,†JPMorgan analyst Haruka Mori said.

[ad_2]

Source link