[ad_1]

China’s pledge last September to become carbon-neutral by 2060 was one of the most striking advances in the climate change battle over the past year. The world had been waiting to see how its next draft five-year economic plan would put flesh on the bones of its commitment. Especially given China’s status as the world’s largest carbon emitter, the plan has turned out to be disappointingly short on substance.

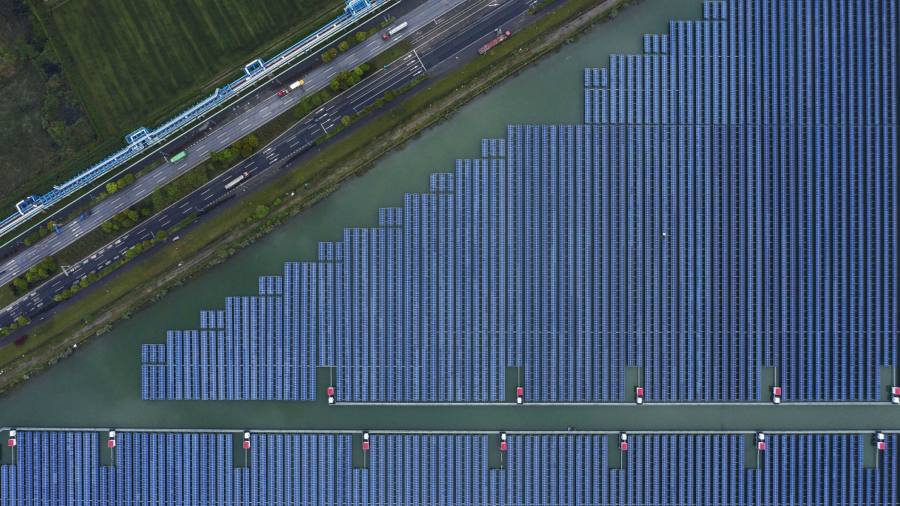

Beijing did set a goal for non-fossil fuels to reach 20 per cent of its energy mix by 2025, from 15 per cent in 2020. Yet that is a relatively conservative aim after China nearly doubled wind and solar power installations last year. Premier Li Keqiang also said a plan to ensure carbon output peaked by 2030 would be completed this year. But a commitment to cut carbon dioxide emissions per unit of GDP was set at 18 per cent, unchanged from the last five-year plan. Analysts estimate that would allow its emissions to continue to grow about 1 per cent a year through to 2025.

International observers had hoped for a far more substantial commitment to move away from coal, such as a moratorium on new coal-fired power plants. According to Global Energy Monitor, a non-profit group, China last year constructed more than three times as much new coal power capacity as all other countries combined. There were hopes, too, that Beijing might set a goal of carbon emissions beginning to fall much sooner than 2030.

China has joined a growing number of countries that have adopted net-zero goals by mid-century or beyond. But experts warn emissions cuts need to be more heavily front-loaded to stand a chance of achieving the Paris Agreement goal of keeping global warming below 2C, and ideally 1.5C, since the 1850s. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has said global emissions must be slashed by 45 per cent from their 2010 levels by 2030 to meet the target, but a recent UN report suggested measures pledged so far would achieve a tiny fraction of that amount. There is little possibility of narrowing the gaping shortfall without China committing to faster progress.

China’s actions have indirect effects, too. If its commitment to hitting its 2060 net-zero pledge is not seen as credible, pressure on other emerging markets such as India will diminish. So might the impetus for fossil fuel exporters to reshape their industry.

Beijing’s failure to set more aggressive goals may reflect resistance from some provinces and industries that insist coal and polluting technologies are vital to ensure growth and energy security. But analysts say reaching peak emissions by 2025 would be not just technically feasible but economically beneficial for China, since solar and wind power costs have tumbled.

Hopes are now pinned on additional steps being announced later this year in China’s first five-year climate change plan, which might yet include, for example, additional curbs on coal. External pressure on Beijing, meanwhile, is likely to intensify. President Joe Biden’s move to return Washington to the Paris accord puts the US and EU back in step on the need for tougher emissions cuts. An updated US pledge expected when Biden hosts a climate summit in April may focus minds in Beijing as it vies with Washington to portray itself as a climate leader.

Momentum is building in both the US and EU towards some form of carbon border taxes targeted at imports from countries that are lagging behind on climate action. Failure by China to make tougher commitments raises the risk that Washington and EU capitals will conclude firmer action on trade is the only way to ensure progress.

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage hereÂ

[ad_2]

Source link