[ad_1]

When he started to pull apart the carcass of China Medical Technologies, which collapsed after a suspected $400m fraud, liquidator Cosimo Borrelli hit an obstacle.

KPMG, which had audited the company from Beijing since it listed in New York in 2005, refused to hand over its financial records. It even defied a court order to do so, citing Chinese security laws that prevent the removal of sensitive documents from the country.

Intent on tracking down the missing money — a senior executive’s wife, it was suspected, had gambled more than $100m of it in Las Vegas casinos — Borrelli hatched a plan.

Over the next two years, his team of eight camped out near KPMG’s Beijing office and took detailed notes of more than 5,000 audit files. KPMG reluctantly granted them access to prevent the liquidators suing 91 of its auditors for ignoring a court order to hand over the documents.

The notes are now being used by the liquidators to sue KPMG in Hong Kong for alleged negligence.

Borrelli and KPMG declined to comment.

The case has become a key contest in the long-running stalemate between China and overseas regulators and agents over access to companies’ financial records. The clash has left the Big Four global accounting firms — Deloitte, PwC, KPMG and EY — which have spent three decades building large operations in the Asian country, trapped between antagonising Beijing or incurring penalties elsewhere.

It is the latest challenge for the Big Four firms, which have faced mounting criticism over their audit quality controls in the wake of frauds at Wirecard, Luckin Coffee and others. They have been threatened by regulators who want to rein in their oligopolistic practices and their global business models face renewed scrutiny.

The spat is also one more flashpoint in the escalating tensions between Washington and Beijing over issues from trade to security, that has already led to the delisting of three Chinese groups and a ban on US investors holding shares in companies with suspected ties to China’s military.

The issue came to a head in March: the Securities and Exchange Commission started to implement a law passed under the Trump administration that compels foreign companies listed in the US to allow America’s regulators to review their financial audits, or face being kicked off its stock exchanges.

In response, China’s Foreign Ministry accused the US of “politicising security regulationâ€, while a wave of Chinese companies has set up secondary listings in Hong Kong to mitigate the fallout.

“The audit firms are caught in the middle of two warring jurisdictions,†said Daniel Goelzer, a founding member of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, the US accounting regulator. “It seems less and less likely China will eventually compromise [with the US], while at the same time China is becoming more important economically for the firms.â€

Worst of all worlds?

Companies listed in the US have been required to submit to PCAOB inspections of their audits since the Sarbanes-Oxley Act was introduced in 2002 in the wake of the Enron scandal.

The number of Chinese companies listed on US exchanges has ballooned since then, and investment in Chinese IPOs on US markets reached record levels this year.

The Big Four, which dominate China’s auditing market, audit about 140 Chinese companies that are US-listed, according to the SEC.

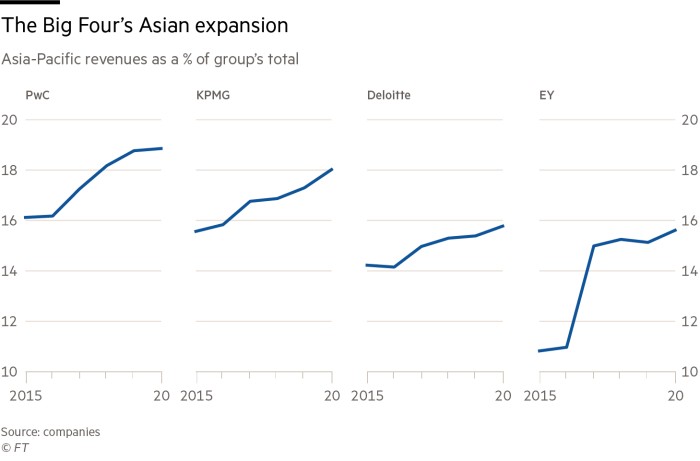

As they have raked in fees from booming internet start-ups looking to access international capital markets, the Big Four’s China operations have grown to nearly the size of their UK bases, employing about 6 per cent of total global staff.

Yet many of China’s largest technology companies such as Alibaba, JD.com and Baidu are among their audit clients that do not make Chinese audit papers available to US regulators.

“The [SEC] provisions are designed to enhance transparency,†said Catherine Ide, vice-president of professional practice at the US Center for Audit Quality. “While the regulatory activity continues, the US audit profession remains strongly committed to maintaining audit quality.â€

If no resolution is reached, the Chinese operations of the Big Four could be deregistered by the PCAOB, blocking them from auditing US companies. The Big Four are also concerned about losing access to the Chinese market.

It could have damaging ramifications for the audits of multinational corporations such as Apple or General Motors that are headquartered in the US and have large operations in China.

“This is not good for the entire auditing profession,†said Paul Leder, former director of the SEC’s Office of International Affairs, who was directly involved in the agency’s engagement with Chinese authorities on this issue. “As a result of the conflict between government authorities in the US and China, auditors face the threat of enforcement actions in both the US and China and the associated costs.

“The current impasse doesn’t serve the interests of the international accounting firms, issuers, investors or the markets,†said Leder, now at Miller & Chevalier, a law firm in Washington, DC.

A ‘golden age of fraud’

Since Sarbanes-Oxley, US regulators have tried a number of ways to force compliance, including negotiating with Chinese regulators and suing audit firms. In 2012, the watchdog took aim at the firms’ China practices over accounting scandals at nine companies that led to billions of dollars of shareholder losses.

Those lawsuits changed the landscape of the profession. Some second-tier firms pulled out of auditing US-listed Chinese companies after their insurance providers stopped underwriting such work.

A recent surge in accounting scandals has pushed regulators to harsher measures to protect investors, including stricter rules for auditors.

“We are in a golden age of fraud,†said renowned short-seller Jim Chanos last year, pointing to Luckin Coffee, the largest fraud by a Chinese company on Wall Street. Mike Pompeo, the US secretary of state at the time, warned American investors of “a pattern of fraudulent accounting practices in China-based companiesâ€.

Local vs global

The Big Four firms market themselves as global entities with a shared culture and consistent standards, but they operate as legally separate franchises. This is particularly an issue in China, where the firms are required to associate with a local accounting firm but still maintain centralised quality control over thousands of audits.

“The structure of the networks is there primarily to protect the group auditor from liability for risks happening outside their home country,†said the head of international audit at a large accounting firm.

A potential solution floated by US lawmakers last year would have required US accountants to “co-audit†the work of their Chinese counterparts. It could have made US partners of the firms potentially liable for the work done by their Chinese partners in the event of a collapse and investor or regulatory lawsuit — something the firms have tried hard to avoid. To the relief of the Big Four, that proposal is “basically deadâ€, according to people close to the talks.

Other solutions are being floated — many undesirable. The head of policy at a Big Four firm said: “We could just end up having duplicate audits all over the world just to satisfy [the SEC] requirement that doesn’t necessarily address quality. I think that’s a risk.â€

However, the existing model has also proved vulnerable to challenge. In the case brought against KPMG over its audits of China Medical Technologies, a Hong Kong judge ruled that all partners of the firm have a “personal obligation to take steps to facilitate complianceâ€, whether they are based in China or not. A similar ruling was made by a UK court against EY Global over its Dubai audit of gold refinery Kaloti last year.

Meanwhile, the Big Four have pledged to try to improve global audit quality standards across their networks, after former SEC chair Jay Clayton last year urged them to improve the quality of the audits carried out in China of US-listed companies.

“Based on the current trajectory of relations between the US and China, it seems likely that the impasse will continue and Chinese companies will move their listings elsewhere,†said Leder. “The Chinese arms of the international audit firms will become less connected to the overall entity as yet one more link will be broken between the US and China.â€

[ad_2]

Source link