[ad_1]

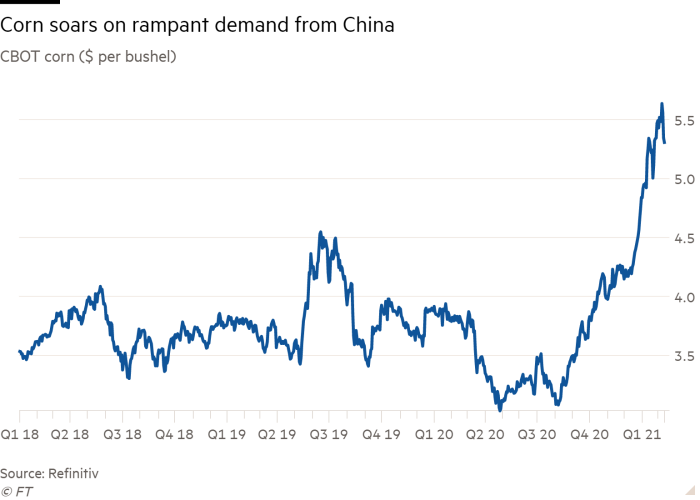

Record purchases by China have sent corn prices soaring since the end of last year, leaving farmers and analysts pondering how long the surge can be sustained.

Rampant demand from the world’s second-biggest economy has driven a fierce rally in grain prices in recent months. China has always been reliant on overseas markets for soyabeans to feed its animal herds. But the ramping up of imports of corn — where the country has previously aimed for self-sufficiency — has surprised analysts and traders.

China bought a record 11.3m tonnes of corn last year, of which more than a third came from the US. In late January, the US Department of Agriculture announced that China had bought another 2.1m tonnes, the largest single sale to the country in history and the second largest on record.

In response, global corn prices have raced above $5 a bushel — a near eight-year high.

“This is a watershed moment for grain markets where new, unforeseen demand of that size was not expected,†said Kevin McNew, chief economist at Farmers Business Network, an online platform for US farmers. He added that at these prices “farmers will see some of the best profitability they have had in the last eight yearsâ€.

With China set to become the world’s largest corn buyer this year, as well as being the top soyabean importer, the big question for the sector is whether the country will stay ahead of other leading corn buyers such as Japan and South Korea.

China’s big purchases of corn come as the country rebuilds its hog herd after a devastating wave of African swine fever a few years ago hit its pig population. Adding to that, the domestic corn industry is now reflecting a decline in plantings several years ago when Beijing halted its corn stockpiling programme and minimum purchase prices. These were initially put in place to encourage self-sufficiency, but led to state inventories ballooning.

Juan Luciano, chief executive of US agricultural traders ADM, told analysts in late January that China would be importing 25m tonnes of corn in future years. “We think that . . . reserves are much lower than what the market is reporting there,†he said.

But others in the industry view the rise in Chinese imports as temporary, especially if trade tensions with Washington continue — and predict that the buying could peter out once the country’s depleted corn stocks are replenished.

Some farmers and analysts in China see the demand as more of a cyclical issue than a structural one. They believe that China’s corn crop in 2020 could be as much as a quarter lower than the Beijing official figures of 261m tonnes due to typhoons and drought that swept across a large swath of northeastern China, a leading growing region for the crop.

“There is no way we can keep production stable given so many negative factors,†said Wang Shanli, owner of a 15,000-hectare corn farm in Heilongjiang Province, who said his farm’s output last year fell a fifth from 2019.Â

Others blame the tight Chinese corn market on hoarding by farmers in the hope of further price hikes. They are betting that depleting state reserves will play in their favour, while taking the risk that further major imports take the heat out of domestic prices.

“I made a mistake of selling my crops all at once in 2019,†said Liu Deli, owner of a corn farm in Jilin. “I am going to take offers gradually this time since there is such an obvious shortage.â€

Traders have also stocked up. Wang Yi, a Jilin-based trader, said he purchased crops from farmers for Rmb2,200 ($340) per tonne and planned to unload his inventory when local prices hit Rmb2,900 (they are currently at Rmb2,800). “If I sell my inventory now, what can I do with my money?†asked Wang, adding that “very few businesses could yield an almost guaranteed return as speculating on cornâ€.

Estimating China’s state and private grain inventories have always been a guessing game for analysts. According to estimates from Sublime China Information, a consultancy, private traders hold at least 100m tonnes of corn. If they start to sell down, they could upset the bullish market.

But with demand for meat and livestock feed growing, and limited ability to increase domestic demand, there is a structural corn deficit, said Pete Meyer, head of grain and oilseed analytics at S&P Global Platts. The gap between China’s production and consumption of corn has been steadily rising in the past few crop years and he expects it to rise to 30-32m tonnes in 2021-22.

Worried about the related increase in feed costs, Beijing has hinted at subsidies to encourage corn production while the high domestic prices are also likely to incentivise planting. However, it could take a few years for acreage to return to the levels seen several years ago, analysts say.

Michael Magdovitz, senior analyst at Rabobank, is bullish about the prospect for Chinese imports for feed grains and soyabeans, predicting demand to continue until 2030, pushing up imports to record levels as well as prices.

“The structural influence and a restocking of animal protein in China is resulting in an import programme that’s never been seen,†he said.

[ad_2]

Source link