[ad_1]

Doctors in Vellore, a city in the state of Tamil Nadu on India’s southern tip, braced for the worst as Covid-19 ravaged the country.

Coronavirus had already battered and overwhelmed healthcare systems across swaths of India and was heading south.

Jacob John, a doctor at the city’s Christian Medical College, said his hospital had approached “breaking pointâ€. Its 900-odd beds had filled up, the hospital was forced to turn away patients and came precariously close to exhausting its oxygen supplies.

But when India’s catastrophic second wave struck Tamil Nadu and other southern states, places such as Vellore were able to withstand the worst of its fury.

That they did so was due in large part to a legacy of investment in primary and public healthcare in the southern states, among India’s most affluent and developed. In many other parts of India, experts said, the chronic neglect of healthcare had been brutally exposed by the crisis.

Tamil Nadu is reporting more infections than any other state, at 22,000 cases and almost 500 deaths daily, while the 900,000 active cases across India’s five southern states account for half of the country’s current total.

“It’s a tough situation. We don’t have enough ICU beds and there are still patients who we can’t accommodate when they come in,†John said. “I’m not saying we’re perfect . . . But when the dust finally settles, I’m sure these investments would have saved lives.â€

Before the second wave hit the south, it overwhelmed healthcare systems in many other parts of the country, including the capital New Delhi and Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state. Patients died because of lack of oxygen and crematoriums were so overwhelmed that bodies were dumped in rivers.

Southern states have experienced their share of tragedy, but experts said they had proved more resilient.

“Because you have a pretty well-developed healthcare infrastructure, the horror stories were not as shocking as they were in other states,†said Ratan Jalan, founder of Medium Healthcare Consulting and a former healthcare executive. “There is that protection which comes into play.â€

India’s southern states account for about 250m of the country’s almost 1.4bn population.

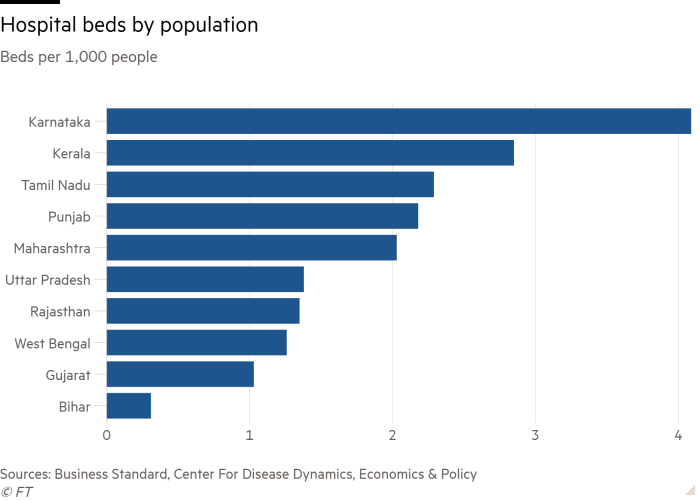

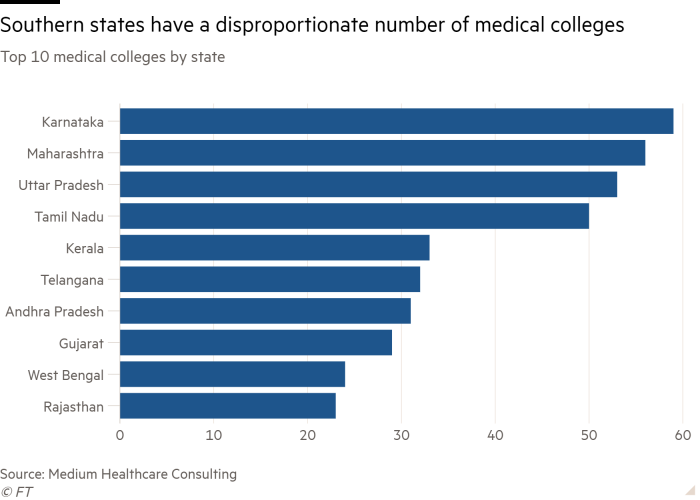

Kerala and Tamil Nadu, in particular, are outliers in healthcare, leading on metrics such as infant mortality. Along with Karnataka, they also boast more hospital beds and medical colleges. India’s southern states dominated the top of the ranking of states by sustainable development released by the UN and a government think-tank last week.

“People don’t have to do the same song and dance to get a hospital bed in Tamil Nadu as in [some other parts of India],†said Lesley Branagan, an anthropologist who has researched Indian healthcare. “That spirit of equity has stayed there over the decades.â€Â

While states such as Maharashtra in the west have also received praise for their response, none has been more lauded than Kerala, the first to detect a Covid-19 case in India last year.

Its early containment of the first wave was so effective that it brought reported cases down to zero on several days in May 2020. Cases surged to more than 40,000 a day last month but have since halved. The number of daily deaths has climbed to almost 200.

Experts said Kerala and Tamil Nadu had tackled the crisis by building on their networks of primary care workers to help the sick find treatment. They have also created “war rooms†to distribute resources such as oxygen, averting devastating shortages.

The high caseloads in the states were also a reflection of better testing, which experts said highlighted greater transparency. They pointed out, however, that undercounting of both infections and deaths was rampant everywhere and the response in parts of the south, including Telangana, has been marred by a lack of clarity.Â

The southern states, as well as Karnataka, went into lockdown last month, and cases have fallen.

Bangalore, Karnataka’s capital and India’s tech hub, is still adding more cases than other large cities.

When the city’s Apollo Hospital opened a 30-bed Covid ward in late April, it was full within 90 minutes, according to Ravi Mehta, head of critical care.Â

It expanded to more than 100 beds, all of which were occupied, and last month came within three hours of running out of oxygen. The pressure has eased, Mehta said, but the hospital’s intensive care unit remains full and it is now dealing with patients with severe complications such as black fungus infections.

“In one month, it [went] crazy,†he said. “We now have to pick up the pieces and give the best care possible to those still struggling.â€

The south’s apparent successes nonetheless conceal deep inequities within the region, with poorer areas enjoying less access to services. At least two-dozen patients died last month when a hospital in rural Karnataka ran out of oxygen. In Goa, the southern tourist hub, scores of patients have died because of oxygen shortages.

Reuben Abraham, chief executive of the IDFC Institute think-tank, said Tamil Nadu and Kerala waited too long to go into lockdown, which had undermined their response.

“Everything will depend on the peak load [that a system can withstand],†he said. “No matter how good your health system — I don’t care if it’s Switzerland or Kerala or the United States — beyond that peak load the system will collapse.â€

PV Ramesh, a doctor and former senior civil servant in Andhra Pradesh, said the crisis should force nationwide reflection over the failure of healthcare across the country.

“This is being seen as an oxygen supply crisis and not a fundamental governance crisis,†he said. “When the wave abates . . . everybody will go back to business as usual and no lessons will be learnt.â€

Latest coronavirus news

Follow FT’s live coverage and analysis of the global pandemic and the rapidly evolving economic crisis here.

[ad_2]

Source link