[ad_1]

Every night funeral pyres blaze on the banks of the Ganges, a grim symbol of the ferocious Covid-19 wave sparking a health crisis and human tragedy in India that is fast surpassing anything seen last year.

Patients are dying while their families search in vain for hospital beds. Supplies of oxygen and medicines are running low, leading to robberies of drugs from hospitals. Crematoriums and burial grounds cannot cope with the sheer number of corpses.

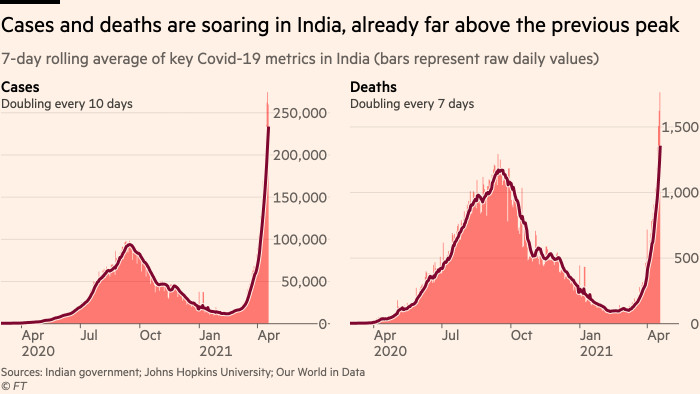

The devastation has sparked outrage at the lack of preparation among officials who believed that the worst of the pandemic was over. Only two months ago, India was revelling in its success of reining in the spread of the virus. Now it is reporting about 260,000 infections and 1,700 deaths a day.

Narendra Modi, prime minister, and his Bharatiya Janata party have been accused of prioritising domestic politics over public health by holding mass political rallies with thousands of people and allowing the Kumbh Mela, a vast religious festival attended by millions, to take place during the second wave.

With a new variant suspected of stoking the surge, experts fear that India is on the same trajectory as Brazil, where a more contagious strain of the virus has hammered the country’s healthcare system and economy.

“Health systems weren’t better prepared for it this time around. Many people in the administration across the country did not expect that there would be a ‘this time around’,†said K Srinath Reddy, president of the Public Health Foundation of India, a charity. “It was somehow presumed that we had passed the pandemic.â€

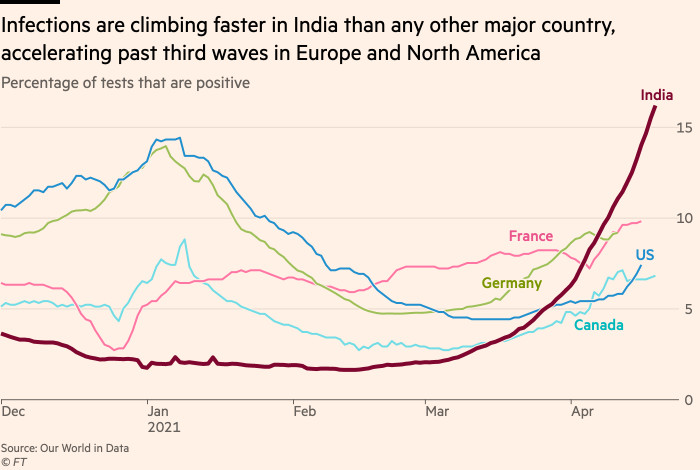

While India’s fatality rate remains relatively low, other metrics betray a deepening crisis. Both the number of new cases and the percentage of positive tests are climbing at the fastest rate in the world, with the latter jumping from 3 per cent last month to 16 per cent.

In the capital, Delhi, which at about 25,000 is recording more new daily infections than any Indian city, the number of cases is doubling every five days.

The sick are overwhelming hospitals in many parts of the country. The rate of ICU patients in Nagpur at 353 per million is higher than it was anywhere in Europe during the pandemic. Mumbai, the financial capital, has 194 ICU patients per million.

To meet surging demand, authorities have set up emergency coronavirus hospitals in banquet halls, train stations and hotels. India has taken emergency measures to secure oxygen supplies, boost production of drugs such as remdesivir and fast-track vaccine approvals. It has frozen vaccine exports, too, a decision that will have profound consequences for the developing world that is depending on Indian manufacturing for its jabs.

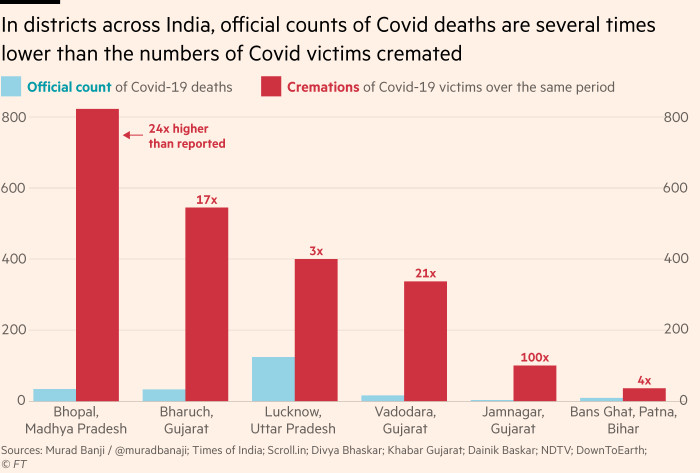

A Financial Times analysis also points to under-reporting of deaths. Local news reports for seven districts across the states of Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Bihar show that while at least 1,833 people are known to have died of Covid-19 in recent days, based mainly on cremations, only 228 have been officially reported.Â

In the Jamnagar district in Gujarat, 100 people died of Covid-19 but only one Covid death was reported.

The situation in Lucknow, the capital of Uttar Pradesh, a state of 200m that is among India’s poorest, highlights how health infrastructure has been pushed to breaking point. Local media reported that at King George’s Medical University, there was a queue of 50 people per hospital bed.

When Shivi Shah’s brother tested positive for Covid-19, she moved her parents into her house in Lucknow.

But it was too late for the couple, both in their 60s. After three days, her father developed blurry vision. The ambulance that arrived 45 minutes later was not fitted with medical equipment to treat him. He died last week on the way to the hospital.

They returned home after struggling to find a place to cremate his body, only for her mother to die in her sleep hours later. “We could have saved our father if we could get a proper ambulance,†said Shah, a 40-year-old school teacher, who along with her son is now awaiting Covid-19 test results after developing fevers. “The situation is quite serious.â€

“None of us suffered the death and devastation that we are seeing now. It is much worse this time than last year,†said Seema Shukla, a nurse at the government-run Sanjay Gandhi Post-Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences in Lucknow. “The condition is so horrible that so many people are dying on the street, in their houses, before they can see a doctor or even have a test.

“From early morning to midnight my phone keeps ringing. Desperate relatives and friends are calling for help: ‘Please help me find a ventilator, bed, a nurse, oxygen cylinder, medicine.’â€

For the Shrivastava family, getting tested and treated turned into a 900-mile odyssey. After his wife tested positive for Covid-19, the son, an IT professional, sent his 72-year-old father and 68-year-old mother back to their home in Deoria, in the east of the state.

After they too fell ill, they had to travel to another city, Gorakhpur, and three centres before they could be tested. They then drove some 400 miles to a suburb of Delhi before finding hospital beds for both parents. The son, meanwhile, remains stuck in Lucknow awaiting his own Covid test report.

“These are the trials and tribulations of those of us who can afford private healthcare,†one family member said. “I can only imagine what’s happening to those who cannot.†The family did not want to be fully identified while their parents remained ill.

Officials are alarmed about the suspected role of new variants in driving the latest wave, particularly the B. 1.617 strain first detected in India last month. Scientists are still trying to understand the variant, which has spread internationally, including to the UK, but some believe it is more infectious and vaccine evasive.

Jeffrey Barrett, director of the Covid Genomics Initiative at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, the research organisation, said the “sheer number of cases†in India pointed to a very sombre picture but “we don’t know yet whether it’s because of this variantâ€.

“You have to look at these things without panicking,†he said, adding that there was not yet sufficient evidence to make B. 1.617 a variant of concern like those first discovered in South Africa or Brazil.

Experts also blame complacency for India’s surge, both among those who rushed back to shopping centres and weddings, and the country’s leaders, including Modi, who have sparked outrage for their electioneering during the second wave.

Yogi Adityanath, the BJP chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, was a star campaigner in the elections before testing positive for Covid-19 last week. Cases in West Bengal, where many election rallies were held, have jumped.

Amit Shah, India’s home minister, told the Indian Express that Modi and the government were “ready, fighting against [the virus] on every front . . . I am confident that we will have a victory over thisâ€.

But Vineeta Bal, of the National Institute of Immunology, said the roots of the crisis ran much deeper, exposing years of neglect of public health infrastructure. India’s spending on healthcare has long lagged behind global peers.

“This is my major problem with not just the current government but the government healthcare system of the past 50 years,†she said. “That’s not going to be solvable in one year when there’s a crisis. This is a steady neglect of many, many years.â€

Santosh Kumar, the son of a BJP leader in Lucknow, has been isolating at home with his family, all four of whom have Covid.

“The entire system has broken down,†he said. “Every other person in the administration here is quarantining. People are finding out from each other what medication to take and doing what they can.â€

Additional reporting by Anna Gross

[ad_2]

Source link