[ad_1]

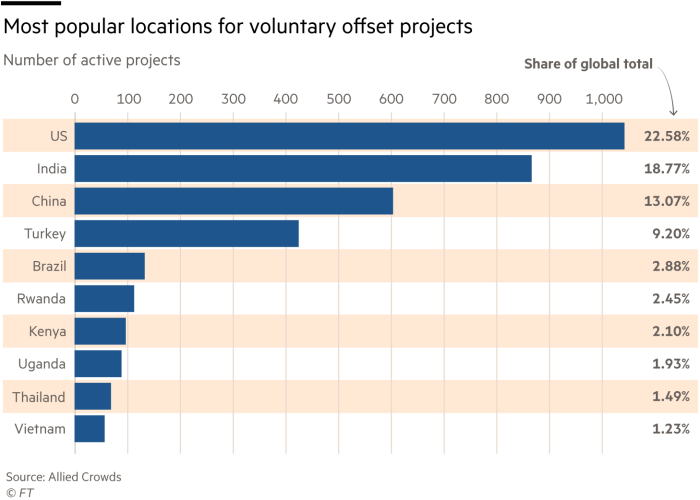

A rush by companies to buy credits to offset carbon emissions has led to contentious schemes being developed by large power companies including India’s Adani Group and US-based NextEra Energy.

Fundamental to the principle of offsetting is that the projects that generate credits should deliver carbon benefits that are additional to a business-as-usual scenario, and be able to show they would not have been viable without the revenue from offsets.

But some of the most abundant credits are from big renewable energy schemes developed by well-funded power groups, according to data compiled by the Berkeley Carbon Trading Project.

As the world races to decarbonise power grids, climate policy experts are questioning the validity of these renewables offsets — which account for about a third of the more than 1bn credits issued to date.

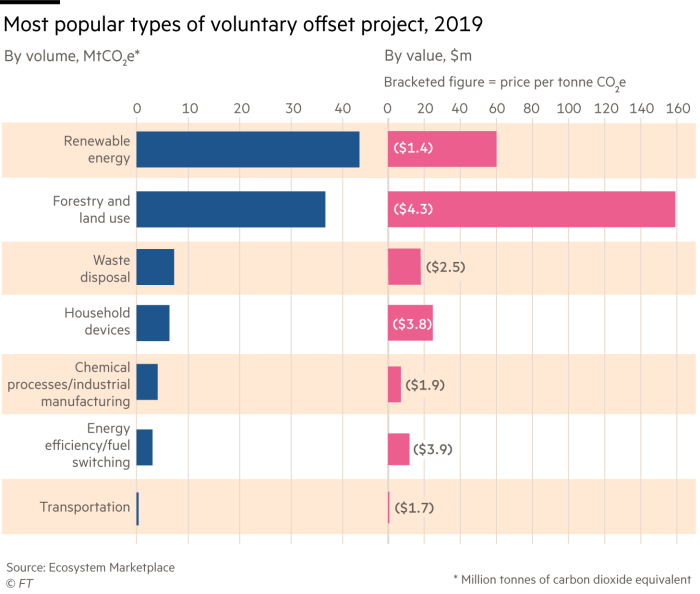

“If you buy carbon credits from a large-scale renewable electricity project you are making zero difference for the climate,†said Gilles Dufrasne of Carbon Market Watch. Since offsets from renewable energy projects were among the most plentiful and cheapest available, companies looking to neutralise their emissions were buying them “whether they have good intentions or notâ€.

For renewable energy projects, the financial test for offset credit eligibility has become more difficult to apply as investor demand and government support for clean energy has accelerated. A 2016 study for the European Commission found that many renewables projects were “unlikely to be additionalâ€.Â

“The revenue from the [credits] for these project types is small compared to the investment costs and other cost or revenue streams . . . Moreover, many projects are economically attractive,†it found.

There are more than 126m renewable energy credits for sale, each representing a saving of 1 tonne of CO2-equivalent, with roughly 191m used since the early 2000s, according to Trove Research. While some of those available were issued more than a decade ago, many were generated in the past few years.

Renewables credits linked to emissions reductions between 2016 and 2018 from large projects in India and China have largely driven the value of S&P Global’s Platts CEC, which tracks the price of credits eligible for the aviation industry’s flagship offsetting system. It has been valued at about $2.10 per metric tonne of CO2-equivalent since mid March.

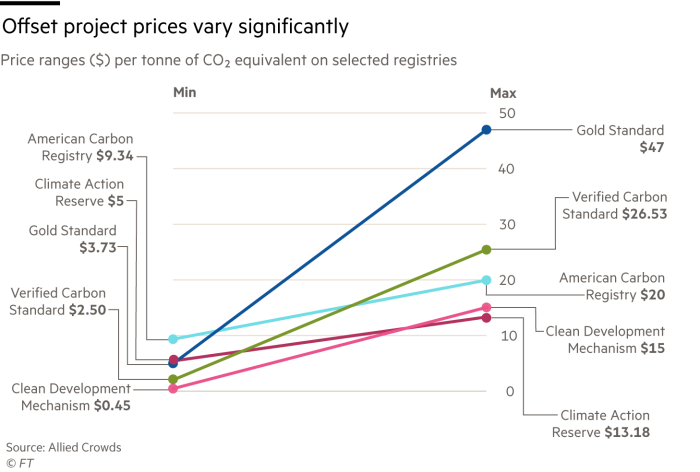

“Most people are going to take the easiest way to transact,†which was often a $2 renewables credit, said Jonathan Goldberg, chief executive of advisory group Carbon Direct. Credits from other project types, such as carbon capture schemes, can cost much more.

Among the renewables projects with the most available credits — 3.1m, according to the Berkeley data — is a solar-power development by Mumbai-listed Adani Green Energy, tycoon Gautam Adani’s renewables business in which French oil major Total has a 20 per cent stake. Adani has said he intends to build the world’s largest solar-power company by 2025.

The project, designed to deliver 990MW of power to five states in India, is expected to produce 15.5m credits over 10 years, linked to emissions savings from 2017 onwards. Recent buyers of the credits include aerospace manufacturer Boeing.

The application to generate offsets was approved by Verra, a Washington-based body that certifies carbon emissions. It says that without the revenue from the credits, the development would have generated an estimated return of only 6-10 per cent for equity investors, below the benchmark of about 15 per cent for energy projects in India — a figure based on a standardised United Nations methodology.

Project documents state that its debt-to-equity ratio was 70:30. Utility-scale solar and wind projects in India are typically “highly leveraged, with average debt-to-equity ratios of around 75:25â€, according to an International Energy Agency clean energy report in November.

In 2019 Adani Green issued $862.5m in green bonds to refinance solar plants. Another Adani solar scheme has been issuing offsets since 2020, and an Adani wind scheme is in the process of registering with Verra.

The same methodology, which in most cases does not consider the financial clout of the project developer, has been applied to two grid-connected solar projects in India by big renewables groups Acme Solar and New York-listed Azure Power, a New Delhi-based solar company. They are expected to produce a combined 30m credits over 10 years, related to emissions savings from 2017 onwards.

Also for sale are half a million credits from a Texas wind farm developed by NextEra Energy, the solar and windpower group that last year briefly overtook Exxon as the most valuable US energy group. The project’s earliest credits related to emissions savings from 2010, but savings made in 2019 produced the greatest number, according to the Berkeley data. Recent buyers include Delta Air Lines and London-listed insurer Hiscox.

Barbara Haya, research fellow at the University of California, Berkeley, said the rules governing which projects could generate offsets should be tightened up “urgently.â€Â

“We continue to produce more and more credits that clearly do not represent real emissions reductions,†she said. Haya’s 2010 PhD on earlier renewable energy offsetting projects in India and China found that “the large majority†were not additional.

Verra and Gold Standard, another certification body based in Geneva, stopped approving most new renewables projects from the start of 2020. Verra said large projects that applied before the deadline were “more frequently rejected†than smaller schemes.Â

“Early [renewables] projects took additional risk and depended on carbon finance to do so — and that investment helped change the space,†Verra said in a statement.

Adani declined to comment, while Acme did not respond to requests for comment. NextEra said it had followed Verra’s protocol.

Azure Power said that while revenue from carbon credits was “small overallâ€, carbon credit sales could allow certain projects to be viable that otherwise may not reach minimum return. “Ultimately, revenue from the sale of carbon credits allows us to provide lower prices for renewable energy to customers.â€

Follow @ftclimate on Instagram

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage hereÂ

[ad_2]

Source link