[ad_1]

Forest Green Rovers in the west of England plans to build the world’s first modern football stadium almost entirely with one of construction’s oldest materials: wood.

The club boasts that the 5,000-seat arena, designed by Zaha Hadid Architects, will be the “most eco-friendly stadium in the world†and support its players’ commitment to veganism.

The football club, which plays in EFL League Two and aims to live up to its Forest Green name, hopes to complete the building of the stadium in Gloucestershire by 2025 in an example of the resurgence of the material.

Demand for wood-based buildings has risen on the back of a drive for green, sustainable products and a surge in home improvements and buying, which have been fuelled by remote working and low interest rates.

Timber companies such as Finland’s Stora Enso and Austria’s KLH Massivholz and Binderholz are set to benefit, with the Nordic group forecasting rapid growth in markets such as engineered timber.

Despite falling by more than half over the past two months as Americans start to go on holiday again instead of renovating, US lumber prices are still trading at $782 per thousand board feet, significantly above their pre-pandemic record.

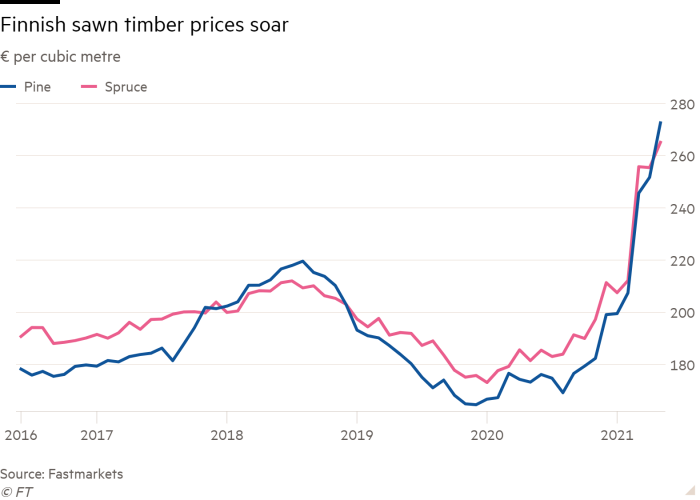

Prices for Finnish sawn timber, a guide for the European market, have jumped 57 per cent in a year to €270 for a cubic metre as sawmills run at full capacity.

Traditionally, wood has been used to build small homes in North America, Scandinavia and Japan. But now governments and corporations worldwide are pushing to expand its use in bigger public buildings, homes and offices.

Construction generates 10 per cent of global carbon dioxide emissions, which wood could help reduce by replacing concrete and steel, while storing CO2 in the building materials.Â

Andrew Carpenter, chief executive of the UK’s Structural Timber Association (STA) expects a big increase in the use of wood, driven by carbon net zero targets.Â

At present, just one house in every four is built in timber across the UK, but the STA expects this to rise to one in three in the next few years after the government’s climate change committee recommended its use in 2019.

France has required more than half of the materials used in all public buildings to be wood or other sustainable materials, while the Welsh government has already decided to use all timber frames on its affordable homes programme from 2022.

Much of the excitement is focused on engineered timber, particularly cross-laminated timber that has many different layers and can be prefabricated in a factory into large sections of a building.

Glulam, another type of laminated timber, can be used for longer spans and heavier loads and offers an alternative to steel beams that is almost 80 per cent lighter.

The new Google headquarters in London is set to be built incorporating cross-laminated timber, while Google’s parent company Alphabet is investing in a timber neighbourhood in Toronto.

David Hopkins, chief executive of the UK’s Timber Trade Federation, says wood also lends itself to off-site manufacturing as it is light and strong and can be erected on site quickly. This should help the construction industry with its labour shortages and poor productivity.

“It’s boom time for timber,†said Hopkins, whose trade federation represents 1,500 UK companies. “There’s a natural living agenda. It improves productivity in the construction process and it’s come back into fashion from an aesthetic point of view.â€

Some housebuilders, such as Barratt, Countryside and Persimmon, have bought up timber frame manufacturers to give them control over their supply chain.

In addition, there had been an increase in timber cladding on a range of mid-to-low rise buildings, helped by changes in US building codes and by architects opting for renewable products, said Richard Waterhouse of NBS, which helps designers identify suitable materials.

The material is also being used for skyscrapers. The world’s tallest timber building is Norway’s 85-metre Mjostarnet tower, while plans have been drawn up for a 120-metre skyscraper made from wood in Vancouver.Â

However, the market for wood has faced some setbacks and failures.

Spiralling costs and financing from collapsed lender Greensill meant SoftBank-backed “mass timber†start-up Katerra was forced to file for bankruptcy in June.

And though Grenfell Tower was not made out of the wood, the 2017 blaze at the London block of flats made policymakers nervous of encouraging the use of timber because it is perceived to be combustible.

Industry figures argue that fire risk fears in wooden structures are overdone, despite tragedies such as the Bradford City football stadium fire that killed 56 people in 1985.

They say, as with all materials, it is a question of how it is installed and treated. “If you do all those things right, it [wood] is a very safe and stable material,†said Waterhouse of NBS.Â

The Forest Green stadium will be treated with coatings that slow the spread of fire, while there will be clear exits designed for quick escape.Â

However, Fred Mills, a former contractor professional and founder of The B1M, Youtube’s most subscribed construction channel, said the material faced an uphill battle to gain traction for use in public buildings in the UK.

“One of the biggest problems is we have a fundamental ingrained cultural preference for concrete and steel,†he said.

“We have a culture of building things as cheaply as we can . . . At COP26 [the UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow later this year], we can’t say we want to lead on climate targets and then keep building with concrete and steel.â€

But, despite obstacles, some groups are pressing ahead with expansion plans as they expect capacity to grow.

Rob Harris, chief executive of Accsys Technologies, which uses industrial vinegar to give hardwood properties to softwood, plans to increase production capacity fivefold by 2025 from 2019 levels after selling enough wood to fill 24 Olympic-size swimming pools in the year to March.

“The shift is phenomenal, but it’s not necessarily policy driven,†he said, adding that the office market was moving quicker than the residential sector in switching to a material with strong green credentials.

[ad_2]

Source link